Today’s article is an excerpt from our recent report:

The Industry Perspective, Engineering Culture and Team Dynamics in a Challenging Environment.

Here we explore the difficulties in pinning down what we mean by ‘culture’, as everyone we speak to tends to have their own take. Our intro below is by no means a definitive or comprehensive analysis, but it lays a few foundations as a springboard to the many facets of culture.

It’s no secret that amidst the layoffs and cutbacks in the Tech Industry during 2023/24, there are widespread feelings of stress, anxiety, and burnout emerging within engineering teams. We have all experienced significant changes over the last few years: the pandemic and the shift to remote working; the ensuing rise in inflation and interest rates which have drastically changed the investment landscape for tech companies; and the rise of mass-market AI tools being applied to everyday engineering problems.

In addition to these sweeping changes within the industry, the wider world is experiencing greater chaos and uncertainty with long-standing geopolitical tensions resulting in devastating wars, rising concerns over the environment and critical ecosystems, and seemingly greater political and social divisions sweeping the nations of the world. The global political and economic outlook remains uncertain as we look forward to 2025 and the continuation of the global order.

The combination of these forces has resulted in an unsettling environment for engineering teams. Teams of people whose personal experience of joy and sorrow intersects with the joys and sorrows of the wider world. And the workplace is where all of these factors come together and intermingle. It’s where the stresses and strains of wider society meet with the personal ambitions and experiences of our work colleagues and with the characteristics and goals of the organisations we work in. From this melting pot of drives, desires, perspectives, goals, and external pressures, through our daily interactions of getting stuff done together, this thing called ‘culture’ emerges.

We know that the prevailing culture we experience is important, not only in how it makes us feel but also in how well we perform. We’ve all experienced that feeling of being in a culture that is utterly draining or restrictive, as well as cultures that feel energising and empowering - but this ‘culture’ thing defies easy description, it can’t be quantified or easily controlled. It is complex and difficult to understand.

What is Workplace Culture?

There are as many diverse opinions on the definition of culture as there are people commenting on the subject.

Is culture those happy team pictures posted on a company’s social media account?

Is it found in the values statements that adorn company walls, brochures and websites?

Is culture encoded in HR policies and the company handbook?

Is it ‘the way things are done around here’?

Is it accurately captured in the words of Bill Marklein who said “Culture is how employees' hearts and stomachs feel about Monday morning on Sunday night”

Does culture really eat strategy for breakfast?

What if I think our workplace culture is great, while my colleague thinks it’s awful?

Culture is intangible

Culture can’t be seen, touched, weighed, or measured. It is something that is sensed by the collective of people within a given social group, but it is sensed uniquely by each individual. It’s a subjective experience yet also a collective experience. So in that sense, it can be described as an intersubjective experience. Culture is represented by the stories we tell, and stories reside in the imagination. The same story is imagined differently by different people. Workplace culture is found in the stories we tell our friends and family about our experiences of work, the gossip and the political intrigue, as well as the fun and our meaningful connections to work. Each person has their own story, each team has their stories, each company is a collection of stories and these all exist in the stories of wider society.

Culture is emergent

Culture is something that arises through the dynamic interactions and interdependencies between the people in the social group. In this regard it is relational, deriving from the way we treat one another and the prevailing social norms. We can’t predict culture by looking at the characteristics of the group members, it is emergent from the integrated sum of the parts. Culture is ever-changing from moment to moment as the nature of our interpersonal encounters changes from moment to moment. Social groups are complex adaptive systems which react and respond to internal and external influences.

Culture is relative

Workplace culture resides in the context of the varying cultures of our wider societies. A culture within cultures. Different countries and different regions have varying cultural traditions which affect people’s expectations of how things should be done at work. Such cultural influences vary greatly over time. Even the most ‘toxic’ workplace cultures in the UK in 2024 would seem quite fair and equitable when compared with the workplace cultures of Britain in the 1970s. One’s experience of culture will vary according to demographics, such as age, race, or gender in terms of personal standards of comparison. Laws and their enforcement change over time and between countries and so do social expectations. One person’s experience of workplace culture is not the same as another person’s as even in the same company experience will vary according to one's role, status, competency, and pay.

Culture is contagious

We are social animals and our behaviours are contagious. Just as one person yawning sets off a chain reaction of other yawns, so we copy our colleagues’ behaviours through the need to conform to social norms. Some people are more influential than others, and this influence isn’t necessarily top-down. We are far more likely to adopt the attitudes and behaviours of our well-respected teammates than to be influenced by a vague set of company values. The socially contagious nature of culture makes it hard to control and coerce. Still, it does mean that we all have some agency in influencing the culture of our ecosystems through the everyday behaviours and mindsets that we bring to work.

How does culture manifest?

Culture makes itself known by the social norms which emerge in everyday work. It manifests as the way a team deals with missing a deadline or the way it celebrates success. It shows up through the way people are supported when they are struggling, or criticised for a misdemeanor. Culture is how behaviours are regulated and how comfortable people feel in taking a social risk. It’s the way we talk to one another, whether honest, direct and caring, or manipulative and insincere. Culture is how we show up for work, whether it is with an engaged sense of purpose or alienated apathy. It’s also how decisions are made: centralised and authoritative, or distributed throughout autonomous teams with a clear purpose and agency. Culture is reflected in the way that information flows through an organisation and the degree to which people are open and transparent. It’s how an ordinary employee feels in the presence of the CEO, and how comfortable they feel in challenging authority. It’s whether someone feels their work has a meaningful impact or whether they merely feel like a cog in a machine.

When the prevailing cultural zeitgeist of the world is somewhat dystopian, polarised, chaotic and uncertain, as it appears to be in 2024, workplace culture doesn’t have to follow suit. While great culture can’t be commanded into existence, those in leadership positions can play their role in influencing the conditions in which people work. And where people thrive, organisations will prosper.

What is Engineering Culture?

Engineering culture is a subset of the overall company culture. The principles, practices and the ways that people show up in the day-to-day activities of software engineering. Each engineering team will likely have their own culture, a micro-climate within the macro-climate of the overall engineering eco-system which itself is part of the macro environment of the wider business and the socio-cultural context of the wider society.

Engineering culture manifests in the way that work gets done and the velocity with which it flows through the value stream and into the hands of users. Let’s look at one small aspect of the flow through the value stream and how engineering culture could be revealed in teams’ approaches to Pull Requests (PRs):

Are PRs reviewed and merged quickly, or do they languish in the queue?

Does it take multiple nudges and reminders to get a PR reviewed?

Are PRs typically in an acceptable state when they arrive for review?

Are PRs promptly approved because everyone is up to speed on what others are working on, or does a lack of context slow the process down?

Do PRs include sufficient documentation (e.g., comments, README updates, or design docs), or do reviewers often lack the context they need?

Are team members hesitant to submit PRs, fearing criticism for incomplete or sloppy work?

Do reviewers dread PRs because they are often large, complex, and unwieldy?

Are PRs approved quickly because the work is of high quality, or are they rubber-stamped after a superficial review?

Is PR review a shared responsibility, or does it fall to just one person? Are product managers or designers involved in the process when relevant?

Is feedback on PRs constructive and actionable, or is it vague and unhelpful?

How do team members respond to PR feedback? Is there a culture of openness and improvement, or do they react defensively?

How does the team handle disagreements during the review process? Are conflicts over code quality or design resolved constructively?

How well are PRs integrated into CI/CD workflows? Are automated tests run on PRs, and how often do they fail?

The work in producing a PR, or any other aspect of engineering, may be technical but the culture of the engineering team determines the behaviours and experiences of engineers as they work together. Engineering work is stereotyped as logical, rational problem-solving, but experientially it can be an emotional rollercoaster which results in fears, frustrations, and anxieties having a drastic impact on the performance of an engineering team.

The musician and producer, Brian Eno, coined the term ‘Scenius’ to describe the cultural scenes from which great advances have been made in science, the arts, and technology from the Enlightenment of the 17th century to the Britpop scene of the 1990s and the IT revolution of Silicon Valley. Each of these examples required a socio-cultural scene for genius to emerge and in software engineering the emergence of our collective genius requires the right scene, the right conditions, the right people and relationships.

Who is Responsible for Culture?

There is no shortage of consultants, coaches, and ‘thought-leaders’ pontificating ways of building good cultures, as well as concepts, models, and frameworks as supposed answers for making cultural improvements. These are widely applied by well-meaning leaders, yet as confirmed by the depressing engagement statistics from the yearly Gallup surveys, it seems that employee thriving and engagement are on a continual decline.

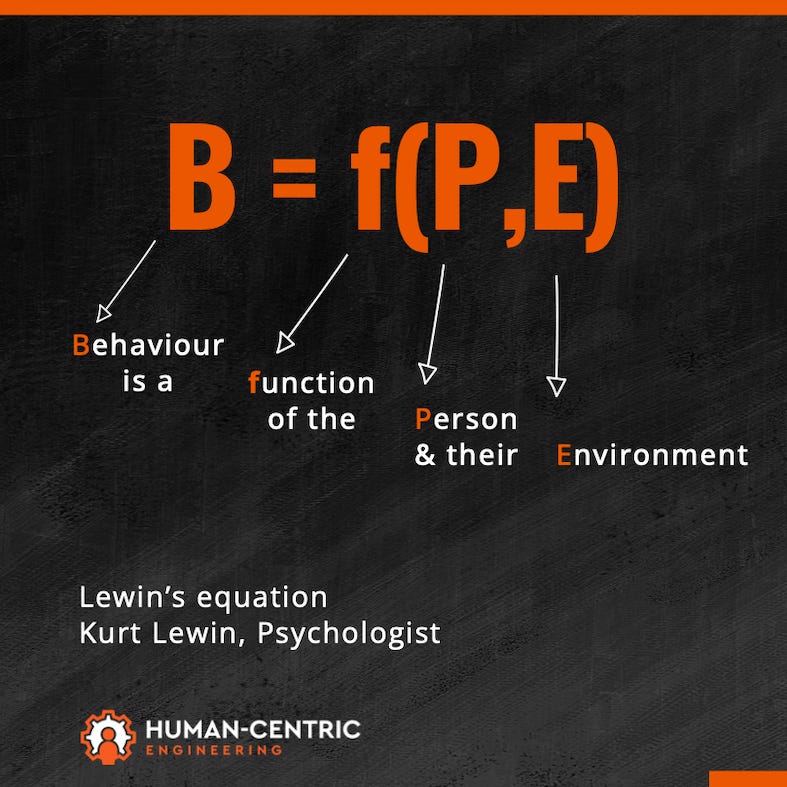

Lewin’s equation - B = f(P, E) - states that Behaviour is a function of the Person and their Environment, as confirmed by W. Edwards Deming, father of the Total Quality Movement when uttering the words “A bad system will beat a good person every time”. Agile was supposed to be the answer but seems to have become saddled with bureaucratic processes where engineers end up going through the motions rather than enabling autonomous and flexible teams to deliver customer value at speed.

Sometimes new people or external consultants are brought in to help ‘fix’ the culture, but we can’t ‘fix’ culture in the way you can fix a bug in the code. There are no silver bullets, 10 easy steps, or cookie-cutter templates. You can only approach culture with a hypothesis and then observe, listen, and try to make sense. Transformation cultural shifts can emerge through the combination of certain chemistries with dramatic results for organisational performance, but it is more realistic to aim for a slight shift in the normal distribution curve of performance.

Culture isn't just an HR thing, a CEO thing, or a framework thing - it's everyone's responsibility, reflected in how we show up, how we relate, and the everyday choices we make. It's a social contagion - the ripple effect of how individuals interact at work and connect with their colleagues. We might sometimes feel like victims of the system but it’s worth remembering we are the system. We have agency through our behaviour to change the beliefs, attitudes, mindsets, and paradigms within the organisation. By recognising this power, we can leverage one of the most potent forces within any system: the hearts and minds of its people. Our actions and interactions create a collective culture, influencing the entire ecosystem in ways that extend far beyond any formal policies or structures.

The participants we selected to be interviewed for our report are people who take a deep interest in engineering culture and are taking personal responsibility for trying to lead in a way that creates the cultural conditions for engineers to thrive and make their deepest contributions.

Our hope is that in sharing their stories, their struggles and successes, we can start a wider conversation about the influence we can all have in the engineering cultures we participate in.

Another deeply thoughtful piece, John, and a great springboard for a culture conversation. I love your "chain reaction of yawns" observation—part of the mimesis we social animals exhibit. It's a great analogy and (intentionally or not) also points to the feeling many have when talk turns to improving the culture. The fact that it is an "intersubjective", experienced both at the individual and collective level makes it complex and impossible to untangle through easy interventions.

That said, we know from our own experience that some people have an outsized influence on those around them, either positively or negatively. And perhaps it's worth looking to those people first to see how we might encourage more (or less) of what they do. I've found Peter Scott-Morgan's ideas on "unwritten rules" insightful here. The triad of "motivators" (what I want), "enablers" (who can help me) and "triggers" (what actions would signal my intentions to those enablers to help me get what I want) can explain why people act in the ways they do. (Hat tip: Geoff Marlow)

Great to see Lewin’s equation here. People often mistake the & between person and environment as two independent parts. But they are interdependent and Lewin was saying how we cannot look at them in isolation. The lowest level of measurement should be person-task-environment (Newell’s Triangle).