The Wisdom of Insecurity

Finding consolation in turbulent times

Times are tough, and many people feel a pervasive sense of insecurity. A nagging worry about the future in the face of exponential change and uncertainty. The tech industry, in particular, feels unsteady as we head into 2025, unsure of the impacts of AI, the prolonged slump in financial prosperity, and the ever-increasing complexity of tech stacks and organisational dynamics. There is a growing sense that the world we once knew is crumbling. Institutions such as governments, media, academia, and corporations, which were once stable and trusted, now seem to be faltering. We have even lost a sense of community that once provided refuge in tough times.

The anxiety many feel leads to a societal cocktail of fear - fragmented communities, political division, social polarisation, worry, overwhelm, burnout, and a growing loss of connection to meaning. We are in the midst of what has been termed the ‘meta-crisis.’

While writing this article I put some feelers on LinkedIn to seek perspectives from other Software Engineers. The insights in the image below from a former colleague, Andrew Baxter - Currently open for work (Clojure/C#/Data) - represent the feelings shared by many in the tech industry:

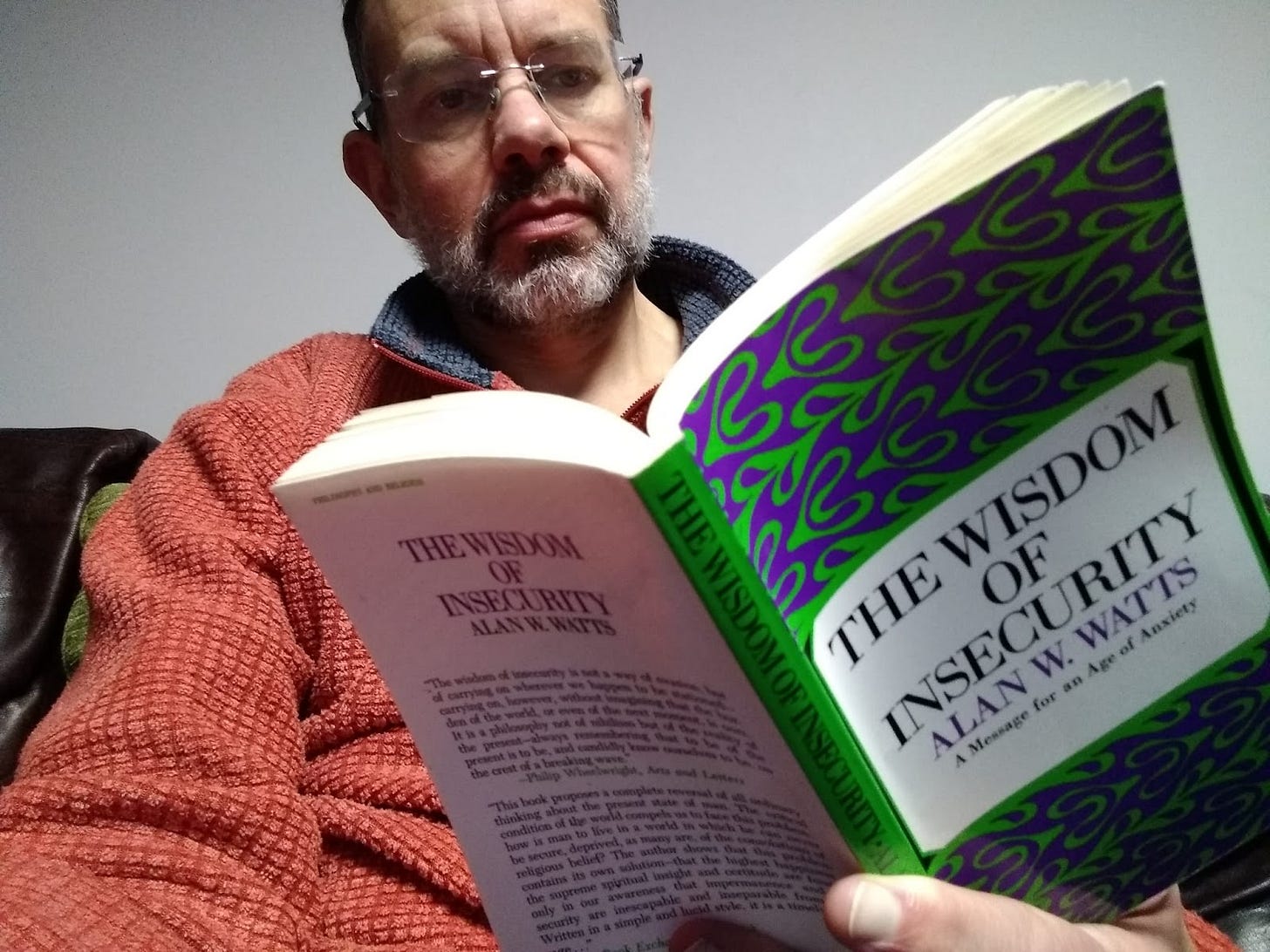

On a personal level, as we are still in the start-up phase of our consultancy business at Human-Centric Engineering, I’m finding the ‘feast and famine’ nature of getting a new business off the ground to be anxiety-inducing. That feeling of insecurity upon waking in the morning, where the monkey mind starts panicking about what needs to be done to generate new business opportunities in a tough economic climate. From a mental health perspective, I’ve experienced periods of depression, which, fortunately, for the last four or five years, I’ve been on top of. But anxiety has crept up on me over the last couple of years - not debilitating, but a continual presence of worry. It has prompted me to re-read “The Wisdom of Insecurity” by Alan Watts, a book that invites us to reconsider our relationship with uncertainty and one in which I found solace about 20 years ago.

I am sharing my thoughts and reflections from “The Wisdom of Insecurity” here because I think it’s an important conversation to have in the tech industry, where so many are grappling with similar anxieties.

Lessons from “The Wisdom of Insecurity”

Alan Watts’ work draws heavily from Zen Buddhism, Taoism, and existential philosophy. He argues that the past only exists in the present, as a representation we conjure in our minds. Likewise, the future is an illusion, pure imagination. Yet, we create our anxieties and insecurities by clinging to these imagined representations as though they are real.

“The more we are able to feel pleasure, the more we are vulnerable to pain - and, whether in background or foreground, pain is always with us.” - Alan Watts

We are born to make sense out of chaos, and making sense means being sensitive. We can reason, hope, create, and love - but the more refined these qualities, the more we tend to experience pain. It may seem that we are living in especially uncertain times, but as Watts argues, our age is no more insecure than any other. Poverty, disease, war, and catastrophe have always been with us. Security is fleeting.

"Human beings seem to appear happy just so long as they have a future to which they can look forward."- Alan Watts

This could relate to the desire for better times in our personal future or the promise of something else, like an afterlife. Watts suggests that as time has progressed, people believe less in the promises of religion, leaving us with “fewer and fewer rocks to which we can hold.”

"If happiness always depends on something expected in the future, we are chasing a will-o’-the-wisp that ever eludes our grasp, until the future, and ourselves, vanish into the abyss of death."- Alan Watts

We have replaced faith in God and the afterlife with faith in science and technology. But the hope we once placed in human ingenuity is crumbling as we fear a looming technocracy that threatens to control and subdue us. As Watts writes: “Logic, intelligence, and reason are satisfied, but the heart goes hungry.”

"For what shall it profit a man, if he shall gain the whole world, and lose his own soul?" – Mark 8:36-38

Watts suggests that “everything composed must decompose.” Every line of code we write will sooner or later be obsolete. This leads many to the nihilism of a world without meaning: “The frustration of having always to pursue a future good in a tomorrow which never comes, and in a world where everything must disintegrate, gives men an attitude of ‘What’s the point anyhow?’”

In this nihilistic world, we are soothed with entertainment. "We crave distraction - a panorama of sights, sounds, thrills, and titillations into which as much as possible must be crowded in the shortest possible time." Overstimulation dulls our senses, and we seek a recursive loop of ever further stimulation.

"To keep up this ‘standard,’ most of us are willing to put up with lives that consist largely in doing jobs that are a bore, earning the means to seek relief from the tedium by intervals of hectic and expensive pleasure."- Alan Watts

All this desire, craving, and attachment to transient things adds to our insecurity. Watts directs us to detachment, to letting go of our craving and clinging. He contrasts belief with faith: "Belief clings, but faith lets go." - we have too much belief in materialistic and abstract things, and not enough faith in the natural flow of life, with all its ups and downs.

Watts suggests that we believe in order to feel secure. He describes this as a futile attempt to “hang on to life, to grasp and keep it for one’s own.” He relates the grasping nature of belief to an attempt to scoop a bucket of water from a flowing stream and wonder why it stops flowing. To ‘have’ blowing wind or running water, you have to let it go - let it blow and let it run. The same is true of life and of our religious conceptions of God.

The Bittersweetness of Life

Watts dedicates a good portion of the book to exploring the bittersweetness of human consciousness. The sensitive human brain adds immensely to the richness of our lives, but there’s a price to pay in terms of our vulnerability. "If we are to have intense pleasures, we must be liable to intense pains." The celebratory joy of deploying a new release is commensurate with the agony of shame when the support team is inundated with critical production issues.

We may seek continuous pleasure, but eventually, we find that "a consistent diet of rich food either destroys the appetite or makes one sick." Joy and pain are opposite sides of the same coin. As Watts wisely suggests, "If, then, we are to be fully human and fully alive and aware, it seems that we must be willing to suffer for our pleasures." If we are unwilling to accept suffering as part of our existence, we close the door to our growth and the development of our consciousness.

Life is a flowing process. We cannot hold on to joy, just as it would be folly to hold on to a crescendo in a piece of music. The crescendo only captivates the senses in the wider context of the rhythm and dynamics of the whole piece. We cannot hold on to a tone and make it last forever. Life flows, ever transient, like the flicker of a flame. We cannot grasp life; we must let it flow from moment to moment. The joy of our successful breakthroughs in solving a complex problem will be compensated with struggles and tensions elsewhere in the emotional rollercoaster of the software engineer.

Pain and Time

At the heart of the human predicament is our consciousness of time, our "marvellous powers of memory and foresight." Watts goes on to say, "For the animal to be happy, it is enough that this moment is enjoyable. But man is hardly satisfied with this at all. He is much more concerned to have enjoyable memories and expectations - especially the latter. With these assured, he can put up with an extremely miserable present. Without this assurance, he can be extremely miserable in the midst of immediate physical pleasure."

This is our predicament. We struggle to enjoy the present moment when we are preoccupied with ruminations about a less-than-happy past or worries about what is to come. Our refined ability to reflect on experiences and plan ahead is key to our survival, but it also handicaps us with everyday insecurities. It is absurd to plan for a future, only to find ourselves “absent” when we reach it, still looking over our shoulder with regret or ahead with trepidation. Our task is to learn to be present in the present moment.

"The growth of an acute sense of the past and the future gives us a correspondingly dim sense of the present… Consciousness seems to be nature’s ingenious mode of self-torture."- Alan Watts

To cling to life is akin to holding our breath. Unless we let our breath go, we cannot take the next breath. The present moment undergoes continuous creation and destruction, just as our sense of self comes and goes from moment to moment. If we try to resist this flow, we are trying to freeze what is inherently fluid, giving rise to suffering and tension. Embracing the impermanence of each moment allows us to flow with life rather than against it.

The Brain-Body Schism

Watts explores how we are divided, relegating the instinctual nature of our bodies in favour of the brain’s rationality. He describes how "we have become accustomed to the idea that wisdom - that is, knowledge, advice, and information - can be expressed in verbal statements consisting of specific directions. If this be true, it is hard to see how any wisdom can be extracted from something impossible to define." Here, Watts builds on the idea that to define something means to try to fix it, but real life is not fixed.

Similarly, at Human-Centric Engineering, we are sometimes asked for template approaches or silver-bullet solutions. Of course, in our unfixed, complex world of software engineering, there are none. We have to immerse ourselves in the complexity and help discover emergent practices for the situation.

Watts describes how we have "been taught to neglect, despise, and violate our bodies, and put all faith in our brains." We are at war within ourselves - the brain desiring things the body does not want, and the body desiring things the brain does not allow. We are in a tortured predicament as mediators between the body and the brain. The brain wants to satisfy the body by imagining a future with continual pleasures but knows it does not have an indefinitely long future. So, to be happy, it must try to crowd all the pleasures of paradise and eternity into the span of a few years.

We can’t smell, eat, hear, or otherwise consume the future because it is "made up of purely abstract and logical elements - inferences, guesses, deductions." To pursue the future as fastidiously as we do, it becomes a "constantly retreating phantom" - like chasing rainbows. The faster we chase, the faster it runs ahead. Happiness is always just around the corner.

Watts describes our predicament as a "sorry-go-round." He writes, "Animals spend much of their time dozing and idling pleasantly, but, because life is short, human beings must cram into the years the highest possible amount of consciousness, alertness, and chronic insomnia so as to be sure not to miss the last fragment of startling pleasure."

He goes on to describe "urban man’s slavery to clocks" - another example of the brain working against the needs of the body. "Our slavery to these mechanical drill masters has gone so far, and our whole culture is so involved with it, that reform is a forlorn hope; without them, civilisation would collapse entirely." The way we allow our lives to be dictated by the unnatural ticking of the clock is yet another example of how we understand so much about the concept of time while distancing ourselves from the very moment our clocks are supposedly measuring.

Awareness

While exploring Watts’ ideas on awareness, I took an interesting detour into the observations of author Steve Taylor on the subject.

Steve Taylor has written several books exploring the psychology of people who claim to have had an experience of spiritual awakening. In his exploration of human consciousness he identifies three modes of attention: abstraction, absorption, and awareness.

Abstraction is when we immerse our attention in our thoughts - the work of software engineering involves spending a great deal of time in this abstraction mode

Absorption is when we immerse ourselves in external objects such as activities or entertainment

Awareness is when we give our attention fully to our experience and our surroundings, and the perceptions and sensations we are having in the present moment.

Taylor observes from anecdotal surveying that people say they spend around 30% of their time in abstraction; 60% in absorption; and only 10% in awareness.

Software engineers, due to the nature of their work, will spend much of their time in abstraction and absorption. Often the advice to take a break, or to create moments of mindfulness goes unheeded - or feels unfeasible when there is a pervasive pressure to perform and always available on Slack. We must create the conditions where it is OK for engineers to balance the demands of problem-solving and productivity with moments of presence, grounding themselves in the here and now rather than being ‘always on’ and always available.

Alan Watts asks “How are we to find security and peace of mind in a world whose very nature is insecurity, impermanence, and unceasing change?” In answering this he suggests we need more light “Light here, means awareness - to be aware of life, of experience as it is at this moment, without any judgements or ideas about it... You have to see and feel what you are experiencing as it is, and not as it is named.”

So for Watts, awareness is a view of reality unconstrained by ideas and judgements.

Awareness is looking at the experiences and sensations we have right now. “If a feeling is not present, you are not aware of it. There is no experience but present experience.” The past and the future are only experienced now. We must “Be here now” as Ram Dass advises. When we think we are looking at the past, we are only looking at “the present trace of the past… like seeing the tracks of a bird on the sand.” From our memories, we can infer the events of the past, but we are not actually ‘aware’ of past events, only the feelings we have right now about the tracks of the bird. The moment is forever dying, and coming into being.

Watts also urges us to see that there is no ‘I’ doing the experiencing, “There is simply experience. There is not something or someone experiencing experience!” The separate ‘I’ Watts suggests, is an illusion, “life is entirely momentary… there is neither permanence or security and… there is no ‘I’ which can be protected”. He adds: “Sanity, wholeness, and integration lie in the realisation that we are not divided, that man and his present experience are one, and that no ‘I’ or mind can be found.”

While reading Watts’ book I posted an ‘#Open to Random Chats” image on my LinkedIn and invited the serendipity of meeting new people. Around 12 people responded and it was great to jump online with them and explore whatever came up. One of these chats was with Kat (Katrijn) van Oudheusden, someone whose daily thoughts on non-duality I’ve followed for the past year. Kat is the author of the book “Seeing No-Self: Essential Inquiries that Reveal Our Nondual Nature” which chimes closely with the subjects I’m exploring here. I’m only partway through the book but there’s a section that has really struck a chord with me which I’m sharing here as Kat has thoughtfully published her book without copyright:

As Kat so eloquently describes - All there is is the container: an eternal, infinite reality that we are. The separate self is an illusion.

Note:

The story of separation

It’s our sense of separateness which is at the heart of much of our anxiety. Johan Hari explored this in his book “Lost Connections” attributing anxiety and depression not to neurochemical imbalances in the brain, as was the common explanation not too long ago, but to our loss of connectedness in modern society. Hari observed the following disconnections:

Disconnection from meaningful work

Disconnection from other people

Disconnection from meaningful values

Disconnection from childhood trauma

Disconnection from status and respect

Disconnection from the natural world

Disconnection from a hopeful and secure future

Hari’s ‘Lost Connections’ can be traced back to what the aforementioned Steve Taylor refers to as the “ego explosion” which he suggests occurred around 6,000 years ago. Taylor claims that humanity underwent a profound psychological shift, which he refers to as “the fall”, marked by the sudden emergence and dominance of the ego. This “ego explosion” transformed human societies, leading to hierarchical structures, environmental exploitation, and a loss of our harmonious connection to nature and with each other that once defined early human existence.

This birth of separation has led to what author Charles Eisenstein in his book “The More Beautiful World Our Hearts Know is Possible” refers to as “The Story of Separation” which has characterised civilisation and has arguably exacerbated in recent years.

This story tells us that we are separate individuals in a competitive, scarce, and hostile universe. It is a story that fuels the ego, perpetuates fear, and creates a societal operating system built on control, domination, and anxiety. The ego, the cognitive abstraction at the centre of this story, the sense of a separate, isolated self, is not inherently bad as it is a useful tool for navigating the world. However, when we overidentify with the ego, we begin to see ourselves as fundamentally apart from others and alone in the universe.

Eisenstein’s work is a call to rewrite the "Story of Separation" and write a new narrative, a story that draws on our interconnection, interdependence, and love, a story of “Interbeing” to use Eisenstein’s term. Such a story recognises that we are not separate individuals competing for scarce resources but integral parts of a living, evolving whole.

We resist letting go of control

It’s hard to let go of our attachments, but the more I muse on my own feelings of anxiety, the more I realise the futility of clinging and controlling. Since my teenage years, I’ve sought counsel and advice from my own personal muse in the form of Jimi Hendrix, sitting on my shoulder, offering thoughts on existence and experience that so often are what I need to hear:

“I know, I know you probably scream and cry

That your little world won't let you go

But who in your measly little world

Are you trying to prove that

You're made out of gold and, uh, can't be sold?

Trumpets and violins I can, uh, hear in the distance

I think they're calling our names

Maybe now you can't hear them, but you will, haha

If you just take hold of my hand

Oh, but are you experienced?

Have you ever been experienced?” - Jimi Hendrix

For me, there’s something profound in these lyrics, beyond the difficulties of the ego thinking it is a material thing made out of gold which we cling to so tightly. Within these lyrics I’m pointed to the idea that I exist, and that we all exist, as a means for the universe to see and to know itself. As Carl Sagan said "We are made of star-stuff. We are a way for the universe to know itself."

Perhaps when Jimi asks ‘Are you experienced’, he’s referring to Sagan’s idea that we are being experienced by the cosmos, by the ultimate reality, by ‘God’ if that’s language you are comfortable with. All there is is experience.

Expanding on this we can use the idea of polarities, the alpha and omega of existence which author Neale Donald Walsh describes in his book “Conversations with God” as the ultimate polarity of ‘Fear and Love’. He posits that fear and love are polarities necessary for the Universe's self-knowledge. We humans exist, suggests Walsh, to experience fear, which creates the necessary contrast for God to experience and understand love. Our journey from fear to love is part of the divine exploration, where choosing love reaffirms the true nature of God, so it goes. Walsh suggests that through everyday acts of compassion and kindness, we undergo a self-remembering, remembering our divine essence. We cannot know light without experiencing darkness.

Living in the Eternal Moment

In the closing chapter of his book, Watts returns to science and religion, suggesting that they are talking about the same universe but with different language. Science is concerned with the past and the future - looking at what has happened and explaining why it happened, then creating hypotheses about what will happen in the future. Religion, by contrast, is more concerned with the present. "Religion is not a system of predictions. Its doctrines have to do, not with the future and the everlasting, but with the present and the eternal."

He suggests this is particularly true of Eastern religious traditions. While Abrahamic religions do promise a heavenly afterlife, there is a common ground underlying the essence of religious thinking across the world’s religions, which focus on the ‘infinite’ rather than the ‘definite.’ "Eternal life is the realisation that the present is the only reality… The moment is the ‘door to heaven.’"

"It is easier for a camel to go through the eye of a needle than for a rich man to enter into the kingdom of God." – Matthew 19:24

Watts adds, "The ‘rich man’ cannot get through this door because he carries too much baggage; he is clinging to the past and the future." Here, Christianity aligns with the ideas of non-attachment from Buddhism. We must be willing to let go of our attachments to live in the present moment. If the present is empty, we crave a future that can never be attained in the present.

To lose our attachments, we must also realise that we must lose our attachment to this sense of “I,” or this sense of self. The ego that we have created separates us from everything else - the stories we construct about ourselves. "So long as there is the feeling of ‘I’ having this experience, the moment is not all." We cannot experience the infinite while we cling to the definite. "Eternal life is realised when the last trace of difference between ‘I’ and ‘now’ has vanished - when there is just this ‘now’ and nothing else."

"The first half of life is devoted to forming a healthy ego, the second half is going inward and letting go of it." – Carl Jung

Watts asserts, "Because the future is everlastingly unattainable, and, like the dangled carrot, always ahead of the donkey, the fulfilment of the divine purpose does not lie in the future. It is found in the present, not by an act of resignation to immovable fact, but by seeing there is no one to resign."

To reduce our feelings of insecurity, we must refrain from clutching at things, clutching at life, clutching at ourselves. We must transcend our feverish intent on explaining, defining, and controlling things and be more at ease with the flowing stream of life.

Watts admires the humble scientist who is aware of their ignorance: “The greater the scientist, the more impressed he is with his ignorance with reality, and the more he realises that his laws and labels, descriptions and definitions, are the products of his own thought. They help him to use the world for purposes of his own devising, rather than to understand and explain it.”

At the heart of the software engineer's anxiety is a desire for control - to know the past and control the future. Writing code is, in many ways, an exercise in creating order out of chaos. Engineers thrive on solving problems, debugging errors, and building systems that work in predictable ways. Can this mindset spill over into our everyday lives which leaves us unrealistic expectations that life itself can be debugged and optimised?

Watts reminds us that life is not a problem to be solved but a mystery to be lived. Life is more of an ongoing predicament that cannot be solved, only managed. The more we try to control the uncontrollable - whether it's the trajectory of our careers or state of the economy, or the technical trends in the industry - the more we alienate ourselves from the present moment. In doing so, we miss the beauty of spontaneity and the freedom that comes from embracing life’s moment-to-moment uncertainties and serendipities.

“The timid mind shuts the window with a bang, and is silent and thoughtless about what it does not know… But the open mind knows that the most minutely explored territories have not really been known at all, but only marked and measured a thousand times over.”- Alan Watts

Takeaways

It’s customary to end an article like this with ‘10 steps to reduce anxiety or other practical quick-wins. But life isn’t a problem to solve, it's an unfolding process of growth. We are all following our unique paths in life and are each faced with unique challenges.

Personally, I will continue exercising, and going out for a run. For me, the rhythm and flow of running is a ‘moving meditation’ that brings me the closest to that in-the-moment state of awareness. I’ll also keep on talking to others about our everyday experiences and struggles. I’m getting the most however from reading authors, philosophers and psychologists who explore the human experience and consistently spending time contemplating the many perspectives on human life.

Instead of trying to predict and control the future, I’ll be trying to trust in my capability to deal with whatever happens next as “life thrusts us into the unknown willy-nilly… the art of living in this ‘predicament’ is neither careless drifting on the one hand nor fearful clinging to the past and the known on the other”, as Alan Watts suggests.

“We don’t see things as they are; we see them as we are.” - source unknown.

We cannot change our reality through overthinking about the past and the future, but we can bend our reality by how we attend to the world and the lens we apply to it from moment to moment.

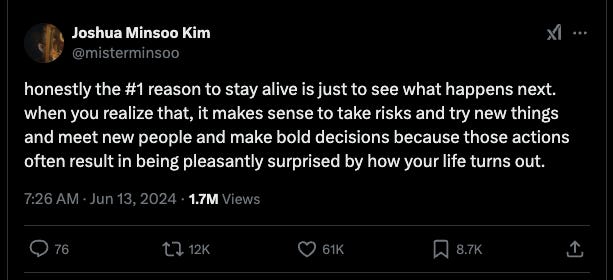

“Honestly the #1 reason to stay alive is just to see what happens next. When you realize that, it makes sense to take risks and try new things and meet new people and make bold decisions because those actions often result in being pleasantly surprised by how your life turns out.” - Joshua Minsoo Kim

There are no special recipes or templates to make feelings of insecurity go away, but we can become more accepting and more at ease with it. If you want help and support in creating the space in your organisation where people feel more comfortable talking about their worries and anxieties, as well as recommendations on addressing some of the systemic and organisational factors which are contributing to people’s sense of insecurity we will be happy to work with you.

Often it comes down to the basics of good communication, good flows of information, stronger relationships, manageable workloads, confidence in asserting boundaries, and clarity of purpose and direction. We have a number of approaches to apply to organisational settings to expose opportunities to improve employee wellbeing and security and would be happy to work with you to devise a customised programme.

During the next 5 years, we may well see more technical and social change than we’ve witnessed in the last 50 years. Whether this manifests as a systemic collapse or a boon in prosperity we will only find out through riding the waves of turbulence, hopefully anchored to the wisdom of insecurity rather than being all lost at sea.

May you live in interesting times.

I finished Tao te Ching last week, now onto Buddha's Brain. Alan Watt's book seems like the next logical choice after this post.

Love the quote:

“We don’t see things as they are; we see them as we are.” - source unknown.

It succinctly sums up the 1000 word post on context I just wrote, in a single sentence.

Thanks for putting this together John, insightful as ever!

Just ordered myself a copy of that Alan Watt's book!

I really resonate with the idea of leaning into uncertainty, as with finding solace in eastern wisdom to help navigate the ever-changing world.

Tai chi introduced me to Taoism, which is the foundation of a lot of my thinking now (software being no exception)

https://engineeringharmony.substack.com/p/what-tai-chi-principles-have-taught