You’re starting a new job, fresh from the interviews and keen to make a good impression and a significant impact. In the beginning, there is plenty of good faith, you’re putting in the hours to understand the unique challenges of the role and learn some new skills where necessary, and you’re excited about your longer-term career development opportunities with your new employer.

Starting from a place of good faith

At first, the organisation seems very supportive, making every effort to make you feel at home and to give you the things you need for early success. But crunch time comes when the honeymoon period is over: you’ve sailed through your 90-day plan, passed your probation - and now what?

If the organisation remains supportive and provides an environment where employees can make their deepest contributions, you are likely to keep showing up as your best self. You’ll be working hard, finding the work rewarding, making progress, getting things done, and celebrating successes with your colleagues.

You may find, however, that the organisation begins failing to deliver on its promises. You don’t have the tools, resources and support that were described during the interview. The culture feels dysfunctional and not at all how it is portrayed in the company’s social media account. Gossip is rife and the lived experience is a far cry from the company values proudly displayed on the company website.

As time passes, and you continue to feel let down by the organisation you respond by slacking off, curtailing your contributions or disengaging completely.

Tit-for-tat

This may be called ‘quiet quitting’ or whatever the latest buzzword is, but in essence, you will decide to do the minimum you can get away with. Why do more when your efforts will not be recognised and your potential impact is quashed by the inefficiencies, bureaucracy, and other pathologies plaguing an organisation that doesn’t seem to care?

In Game Theory terms, this scenario illustrates a tit-for-tat strategy, where your actions mirror the behaviour of the other party - cooperating when the organisation supports and invests in you, but withdrawing effort when the organisation fails to uphold its commitments. This reciprocity may protect you from exploitative burnout, but it also creates a downward spiral of ruinous misery for both parties if it goes beyond the point of being able to re-establish trust and mutual goodwill.

The employee’s dilemma

Let’s frame this employer/employee decision dynamic as a version of one of the most well-known examples from Game Theory, The Prisoner’s Dilemma.

Game Theory is a mathematical framework which emerged in the 1940s through the work of John von Neumann and Oskar Morgenstern looking at how individuals and organisations make strategic decisions under conditions of uncertainty and competition.

The Prisoner's Dilemma is a classic Game Theory scenario that shows how two rational individuals might not cooperate, even if it appears to be in their best interest to do so. In the scenario, two suspects are arrested and interrogated separately. Each has the option to either betray the other (defect) or remain silent (cooperate).

If both suspects trust one another and cooperate, they each receive a light sentence.

If one defects while the other cooperates, the defector is set free while the cooperator receives a harsh sentence.

If they both defect, they each receive a moderate sentence.

This dilemma highlights the tension between self-interest and mutual benefit, often leading to suboptimal outcomes when trust is lacking - a common experience in the dynamic of workplace relationships.

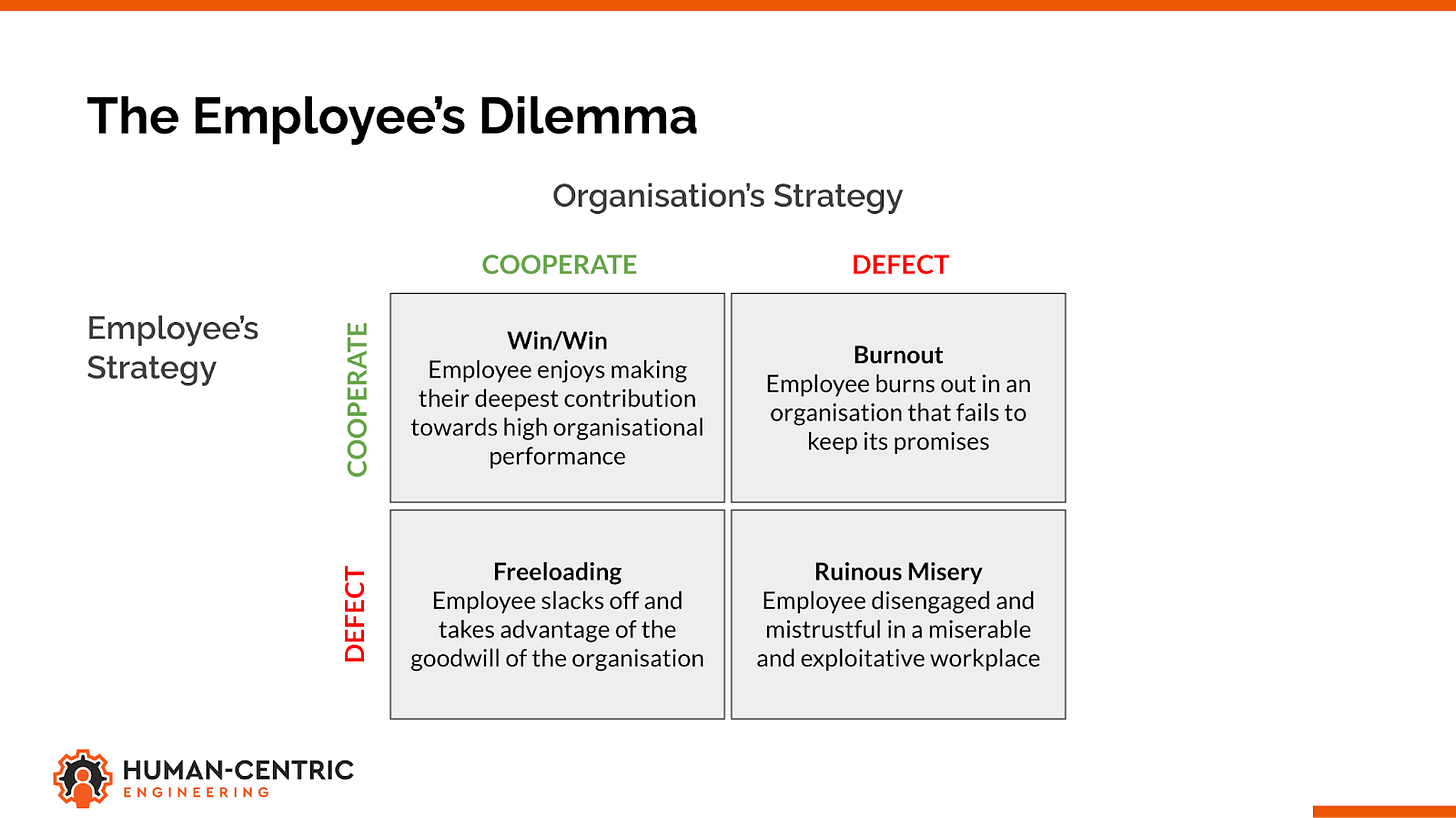

Let’s call this The Employee’s Dilemma to throw some light on the strategic predicament of the employee/employer relationship.

The quadrants and the strategic outcomes

Let’s examine how workplace dynamics might map onto the quadrants of the Employee’s Dilemma.

Win/Win - The employee and the organisation cooperate

The rational approach for both the employee and employer would be to trust one another and cooperate.

The employee puts in effort, delivers value, and earns a reputation for high performance and competence to advance their career prospects. The Job Demands-Resources model (JD-R model) suggests that the high challenge associated with the pressure of a demanding job can be rewarding for the employee when they are given sufficient resources and support. This is also corroborated by Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi’s work on the ‘flow state’ where an individual feels ‘in the zone’ when stretched by the right amount according to their skills and the support available to them.

The organisation benefits from engaged employees who derive a sense of meaning from making deep contributions to aid organisational performance. As per the findings in the book Accelerate: The Science of Lean Software and Devops: Building and Scaling High Performing Technology Organizations, culture is predictive of organisational performance, an organisation which chooses the ‘cooperate’ strategy by focusing on creating the kind of humane working conditions in which individuals can thrive yields downstream commercial benefits.

Burnout - The employee cooperates but the organisation defects

If the employee continues in good faith to perform at their highest level but the organisation reneges on their side of the deal, the employee risks burnout and regret over the naive trust placed in their employer.

This would be especially difficult for the employee if they are eventually 'let go' by the organisation when they're no longer needed, perhaps being a wake-up call resulting in a bitter resolve to never be taken for a fool again. Such sentiment is not uncommon following the brutal layoffs in the tech industry during 2023-24 - perhaps a sentiment that has long-term consequences yet to play out.

While the defecting strategy of the organisation may help protect the bottom-line revenues and profits in the short term, the reputational damage to the organisation, the risk of losing institutional trust, and the human cost of stress-related illness may hamstring the organisation’s future prosperity.

Freeloading - The employee defects while the organisation cooperates

The employee puts in minimal effort to keep their job and collects their monthly salary. An easy life where other people are left to pick up the slack. The employee is LARPing, pretending to be engaged or busy without actually doing substantive work. This is the pretence of ‘busyness’ we often see in workplaces. As long as they can keep up the act, the employee is rewarded by being overpaid relative to their minimal contribution.

But this strategy doesn’t serve the employee in the long term as they will stagnate and risk feeling bored, depressed and apathetic. If the organisation is making every effort to provide career development opportunities, good compensation, psychological safety, and an environment where the employee can make their deepest contributions then it may be more rational for the employee to switch to a cooperative strategy - boosting their own long-term prospects while feeling like they are making a meaningful contribution.

Ruinous Misery - Both the employee and the organisation defect

The worst of all worlds, and a widespread situation in modern workplaces, is where both the employee and the organisation choose to defect, leading to an awful pit of despair which sucks the vitality, joy, and prosperity from the workplace dynamic.

Cost-cutting organisations burdened with bureaucracy and an extractive approach to their ‘human resources’ are all too common, contributing to widespread institutional mistrust. With ever-growing disparities between CEO and worker pay, and the prioritisation of shareholder value above all else, many organisations are in a ‘race to the bottom’, neglecting the needs of employees and customers, to meet quarterly revenue targets. Return-to-office mandates are often used as an alternative to honest and fair redundancies, further alienating employees. In such an environment, it’s little wonder that many choose disengagement as a response to feeling undervalued.

Both the employee and the organisation maintain the performative stance of ‘playing the game’, appearing to be committed to one another - entwined in their disingenuous manoeuvres in a dance of disharmony. We see it in the exaggerated social media profiles of employers, and the exaggerated LinkedIn posts by employees. This results in a tragic low-integrity scenario of mutual deception and long-term self-sabotage, performative game-playing on both sides which merely prolongs everyone’s misery in a cynical Post-Truth world.

Disengagement becomes socially contagious as both parties settle into an unhappy compromise where the employee and the employer feel stuck with their current strategies. The organisation continues to extract as much as possible from the employee while providing minimal investment in their well-being or development, and the employee continues to disengage in order to maintain the status quo, seeking only to avoid repercussions. It becomes a social norm that both parties learn to accept. The employer expects low trust and minimal emotional investment, while the employee accepts their learned helplessness in exchange for a little job security and a monthly salary while longing for retirement. The organisation stagnates, while employees grow ever more disillusioned, trapped on the Sisyphusean treadmill of performative "busyness".

Such a collective resignation exacerbates the breakdown of mutual trust, leading to workplaces and a wider society that perpetuates the cycle of dissatisfaction and disengagement.

Escaping ruinous misery

The true picture is nuanced and may not be as bleak as I’ve presented here in this rather simplified application of game theory to extremely complex employer/employee dynamics. There are leaders who care, teams that thrive, and plenty of employees who sincerely want to make a worthwhile contribution. Many books in the tech field point the way to effective human-centric leadership styles, which prove the value of creating the conditions for mastery, autonomy, and purpose in the workplace.

The idea of the employee’s dilemma quadrant and the scenario where both the employee and the organisation cooperate for mutual advantage shows us the win/win we should strive for. But we can only get to that place through an honest and open dialogue from where we tend to operate right now.

The way out of Ruinous Misery is for the organisation to take the initiative and begin by building trust. Organisations that tackle this head-on with an attitude of continuous improvement have much to gain in terms of competitive advantage and long-term prosperity. When employees see that an organisation is intentionally improving its culture the effect of social contagion brings everyone along for the ride.