A case for prioritising your Luck Surface Area

The how and why of engineering more luck and opportunities into your life

Do you think of yourself as lucky or unlucky? What if there was a way to engineer more luck into your life? Is that even possible?

I believe - from experience - that it is possible. And this article is part how, part why, and part my story. How I came to get book deals, get involved in the most interesting projects at work, and meet new business partners. And it’s not just direct experience, it also makes logical sense.

This article is inspired by

’s recent article How To Create Your Own Luck, talking about Luck Surface Area. “Luck Surface Area” is a phrase that jumps out at me whenever I hear it because it’s this very phrase that set me on a new path back in 2011. I first came across the concept listening to the Techzing podcast from Jason Roberts and Justin Vincent on my commute. Jason Roberts coined the idea and wrote about it in 2010.Luck Surface Area

First up, what is Luck Surface Area? The concept is that each of us has this surface area of luck, where the greater the surface area the greater our luck. And, of course, with more luck, we have more chances of good (unexpected) things happening to us. Your Luck Surface Area is the amount of serendipity in your life.

And who doesn’t want more good things happening to them?

In his own words (emphasis is mine), Jason says:

“Luck Surface Area, is directly proportional to the degree to which you do something you're passionate about combined with the total number of people to whom this is effectively communicated. It's a simple concept, but an extremely powerful one because what it implies is that you can directly control the amount of luck you receive. In other words, you make your own luck.”

He then expressed this as a simple formula:

Luck = Doing * Telling

So the really short version is: you can increase your Luck Surface Area - the serendipity in your life - by doing stuff and telling people about it.

Naturally, it’s a little more nuanced than that, as evidenced by the words Jason chose to describe it.

Doing stuff

The keyword here is authenticity. I find the word “passion” problematic and overused, but you do need to have a genuine interest in what you are doing. We all subconsciously drift towards the people who are authentically interested in whatever it is they’re doing and telling us about. It’s one of the reasons why original “creators” outlast and outperform copycats - they are genuine and we can tell.

In some ways, it doesn’t even matter what you do so long as you clearly have this authentic, inherent interest. I mean, we all have to tidy our homes and fold our laundry, but unless you’re as into it as Mari Kondo your lack of genuine interest will soon become apparent to others.

Also, depending on what you’re doing, you don’t even need to be an expert - as you’ll shortly see from my story. But you can increase the Doing component by ensuring that whatever you’re doing, you’re doing well.

Telling people about it

This one’s the kicker, especially for most of us engineers. This one is about - as Jason says - effectively communicating what you’re doing to as many people as possible. Note that there’s quite a difference between “telling people” and “effectively communicating” - effective communication relies on other people understanding what you say. You want them to retain it, share it, and recommend it to others. You want to make an impression.

Engineers often have a hard time doing this for people who aren’t technical in the same way, but it is a skill to learn and definitely worth the practice.

The engineer’s pitfall

This is something of a sweeping generalisation, but us software engineers tend not to crave the limelight or enjoy putting ourselves out there. Whilst we do crave recognition, we do not desire mass attention.

I have noticed a fairly pervasive belief throughout the engineering ecosystem that the work should speak for itself, and that recognition, reward, and opportunity should follow. One could certainly argue the case for this, but sadly this is not reality, much to the chagrin of many a miffed engineer.

The reality is that we may gain a little recognition and respect from those around us, but the exposure is limited, the reach is limited. The best case is that somebody else - perhaps a project manager or product owner - sings our praises, and the awareness of our capabilities and the impact that we can have spreads a little further.

Many of my side projects and ideas have been somewhat limited in their success due to my leaning towards a “build it and they will come” mentality. I’ve always known it’s not true, but after all of these years, that lesson is fully baked into me.

Case study: Simon Holmes, aka me!

Way back in 2011, I found myself wanting to change things up a bit. My default tech stack was ageing and somewhat locked into the Microsoft ecosystem, and I wanted to change my career direction from working in an agency towards a product-led company.

Listening to the Techzing podcast on my commute, Jason Roberts was talking about his concept of Luck Surface Area and the idea struck a chord with me. But the Techzing influence didn’t stop there. Jason was very early in at Uber and talked about how he’d built the original dispatch server in Node.

Connecting the two dots, he went on to recommend an idea for people looking for new opportunities. Pick a new technology that you think will take off - his suggestion was Node of course - and start blogging about it.

This was all the inspiration I needed. It ticked the boxes for me. On December 29th, 2011 I blogged about my intentions to start learning about the Node ecosystem and blogging my journey. (I forgot to renew my domain during my divorce a few years ago and it was sniped, so thanks to the Wayback Machine for this URL)

Learning in public

My “doing and telling” in this case was essentially me blogging my learning journey. Perhaps importantly, it wasn’t just random snippets. There was a flow with a purpose, giving it all a sense of cohesion.

I clearly was not an expert. But what I was doing and how I communicated that resonated. No doubt having more than a decade of professional experience by that point certainly helped. I wasn’t an expert in the specific subject matter, but I was very experienced in the craft of building full-stack applications. As a side note, learning in public is a great way of forcing you to learn something to a deeper level. When you’re explaining everything you can’t get away with “and doing it this way works, I’m not sure why, but it works”.

Juggling a new job, a new baby, and a new blog, I posted persistently if not consistently for some time.

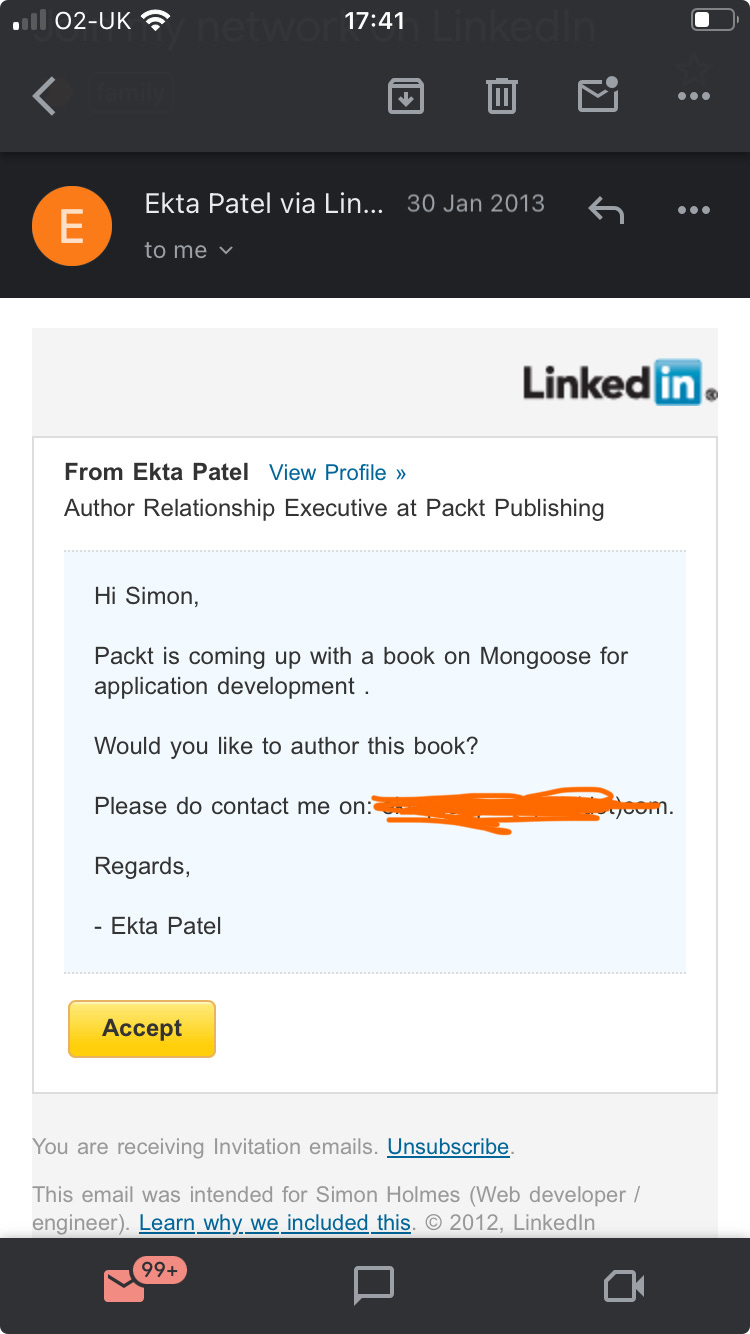

One year, one month, and one day after that first post - on January 30th 2013 - I received a random connection request on LinkedIn from an acquisitions editor at Packt Publishing. They had seen my blog and wanted to know if I was interested in becoming an author and writing a book on Mongoose.

A totally unexpected opportunity and not something I’d ever thought about. I’d never harboured dreams of becoming an author. My (then) wife, however, had. She’d been writing novels ever since I met her, but nothing published. Was I just lucky? She certainly thought so. (I’m pretty sure this wasn’t a contributing factor in our separation a few years later…)

But it doesn’t end there.

A double dose of luck

A few months later - June 2013 - as I was approaching the end of the first draft of the Mongoose book (it’s a relatively short book) I was approached by a different publisher, Manning. They too had found me through my blog, and wanted to discuss whether I’d be interested in writing a book about Node/MongoDB/Express. And they had no idea about the Mongoose book currently in the works.

And this is where Getting MEAN was born. It ended up becoming - in tech terms at least - something of a best-seller, and was even used by a few institutions as a text book.

Lucky again? Perhaps. But I had set out 18 months earlier with the sole intention of increasing my luck and the number of opportunities that came my way.

But it doesn’t end there.

New business opportunities

Manning also believe in a doing and telling approach, building in public if you will. Their books enter a Manning Early Access Program after the first three chapters are drafted. At this point they start promoting the book and readers get to read your drafts as they are published, can ask questions and provide feedback.

It was during this process that I met my first business partner. He was a technical trainer, very into web technologies. We got talking and in early 2014 decided to start the “Midweek MEAN Stack” meetup in London. By the end of 2014, we had established a training company with courses in full-stack development and single-page applications with Angular. Remember, this is when Angular was new, cool, and somewhat magical.

Was this luck? Or more a function of doing and telling?

Doing and telling at work

While all of this was going on, I was also working full time, progressing from engineer, to manager, to director. But I also embraced the Luck Surface Area concept in work. I personally think this is a great place to get started if you’re fortunate enough to be in a company of the right size and mentality.

The inflexion points for me here are smaller and less obvious than my ‘blogs’ to ‘books’ to ‘training company’ trajectory. But the aim is the same: build a reputation and invite opportunities.

Most people at a company don’t do this. Especially engineers. As I mentioned before, self-promotion is not a natural trait for engineers, and the need for it is met with some distaste. I get it. I’m the same, I feel the same way.

Yet if you don’t do it, you’re unlikely to get the recognition that you deserve.

The three main things I did were:

Volunteer for cross-team projects

Build tools that helped me and others internally

Get involved in the company intranet, sharing ideas, experiences, and solutions

And one crucial thing - let your baby fly free. Share what you’ve done and invite others. If you become a bottleneck you close yourself down to future opportunities.

All of this together helped me to build a great reputation in all areas of the company, all of the different regions and all of the different departments. It led to numerous opportunities and interesting projects, pay raises and promotions, retreats and offsites with the C-suite, and special projects with the CEO and Board of Directors.

Was this luck? Or luck generation?

Getting lucky, attracting opportunities

The concept of Luck Surface Area - and your ability to increase it - has power in its simplicity. And it’s enticing to think that we can have a hand in creating our own luck.

But why should you care, and why should you want to do anything about it?

Take your pick:

Personal and professional growth

Giving yourself more opportunities and options

Challenging yourself and realising more of your potential

Having greater impact on the world around you

Helping others learn and grow

Opportunities come from people trusting that you can help them in a particular way or help them solve a problem they are currently facing. The people in your immediate network likely know what you have done and what you can do, without too much direct telling. The people in your second- and third-degree networks at work are your low-hanging fruit.

To generate more opportunities - i.e. increase your luck - you need to scale up this sense of trust to wider networks. You want to bring people on a journey with you, and have them on your side. And this can work both inside and outside your current company.

You never know when opportunity will come knocking, or what that opportunity will be.

"Share what you’ve done and invite others. If you become a bottleneck you close yourself down to future opportunities." Great point, Simon. Congratulations on the two books. No doubt a third opportunity will emerge :)