Games Engineers Play

The psychology of engineering relationships

This is not an article about Fortnite, Call of Duty or Doom, it’s an exploration of the seminal work by psychiatrist Eric Berne in his 1964 book ‘Games People Play’.

Berne studied the unwritten rules that occur in social and team interactions. He viewed the dynamics of certain interactions as ‘games’ where we keep score and transact points. His interest in the dynamics of our personal encounters led to the development of the psychological framework of Transactional Analysis.

I’ve often struggled in social situations, especially when I was younger. I detested small talk. I was comfortable with close friends but with no interest in football, rugby or sports cars I was at a loss at what to talk about at parties or any social gathering with strangers, so I avoided these events altogether or would subdue the experience with alcohol. I was especially baffled by the social affiliations people made at work and the combative shenanigans that went on. So I studied people and social situations myself, with the aid of whatever books I could find to throw light on the incomprehensible nature of people and relationships. Berne’s ‘Games People Play’ is a gem of a book I first encountered about 25 years ago, and it has stayed with me.

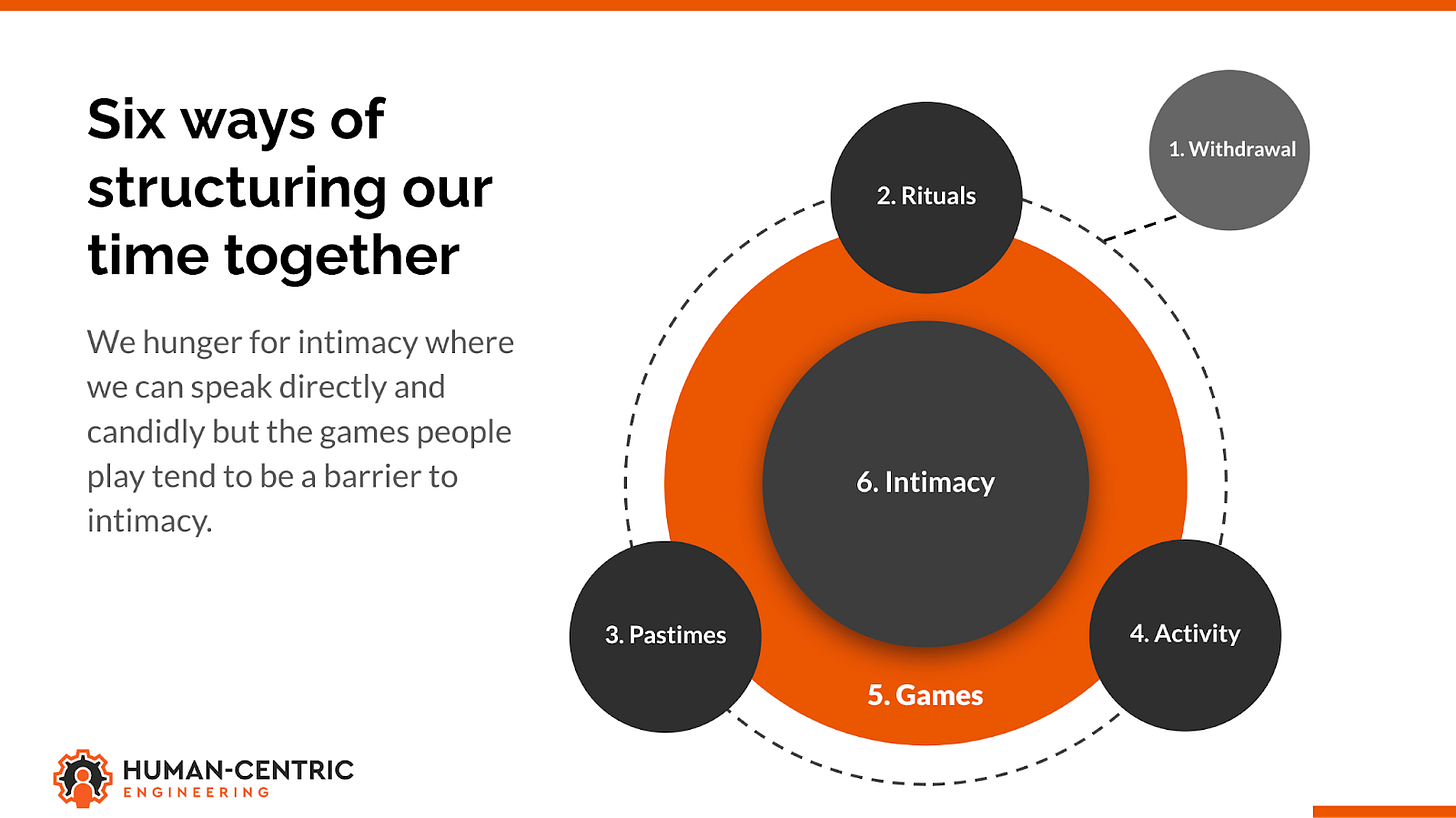

Eric Berne suggests that there are 6 different ways of passing our time with each other during social interactions.

What we’re all seeking is intimacy in our social interactions, but depending on our disposition and the social context we tend to adopt less satisfying approaches.

1. Withdrawal:

We can choose to withdraw from the interaction, either physically or through presenteeism. Withdrawal can be healthy or unhealthy, depending on the context - e.g. daydreaming or retreating when socially drained.

2. Rituals:

These are the everyday pleasantries of “Hello, how are you?”, “OK, thanks - though it looks like it might rain again.” - and so it goes… Rituals are fairly predictable, and highly structured but surface-level conventions, conforming to the prevailing cultural norms.

3. Pastimes

Pastimes are semi-structured interactions around safe subjects, perhaps discussing sports teams, celebrities, holiday plans, or non-contentions current events. Time is passed together with a pleasant and low-risk feel. Games People Play was published in the '60s, and some of the colloquialisms in the book reflect the established social norms of the times. With pastimes such as ‘Wardrobe’, ‘Grocery’, and ‘Kitchen’ positioned as Lady Talk, and ‘General Motors’ and ‘Who Won’ as Man Talk, it’s fascinating to observe how society has changed over the last 60 years.

4. Activity

Activity relates to people coming together around a shared goal. Coming together at work for standup meetings or retrospectives with teams working together on a project. Our shared hobbies create activity-based relationships - collaborating on Fortnite, attending a fitness class or playing 5-a-side football. The focus is on the collective purpose and relationships develop obliquely to the shared pursuit.

5. Games

When social interactions are laden with drama and complex ulterior motives. When we see the emergence of the persecutor, victim and hero dynamic. When there are hidden and manipulative plays for status, we are probably in the dynamic of games. Games trigger our emotional reactions, the fuel for soap operas and modern politics. They are the source of frustration, anger, and resentment. We get locked into repeatedly playing the same games over and over, stunting our growth and diminishing our relationships. Games prevent us from getting to what we really want, which is social intimacy - but we play them because there’s always a payoff: they reinforce our existing beliefs about ourselves and others and protect us from the vulnerability required for true intimacy, thus maintaining a sense of control and predictability in our social interactions.

6. Intimacy

We want authentic and open exchanges with genuine intent. A sincere emotional exchange without any hidden agendas. This is where we share honest interests and genuine concern for one another and can explore nuanced topics or discuss difficult challenges in good faith without feeling personally threatened. This is the domain of true psychological safety where we share our fears, failures and true aspirations.

“Pastimes and games are substitutes for the real living of real intimacy.”

- Eric Berne, Games People Play

Transactions and strokes

Transactional Analysis is the idea we are exploring that social interactions can be viewed as transactions and that these transactions conform to predictable structures.

Berne suggests a unit of social currency called a stroke that we keep score with. If I meet you in the street and say ‘Hi’ I’ve given you a stroke, like a stroke to your ego. When you say ‘Hi’ you’ve paid me back. We might break the exchange there and all is well. But if you’ve recently been away on holiday for some time, and I forgot to ask you about it - you may feel affronted, I’ll be a debtor in your strokes balance sheet. Had I asked you about your holiday then I’d have given you the five strokes you had expected and our exchange carries on fairly in your mind.

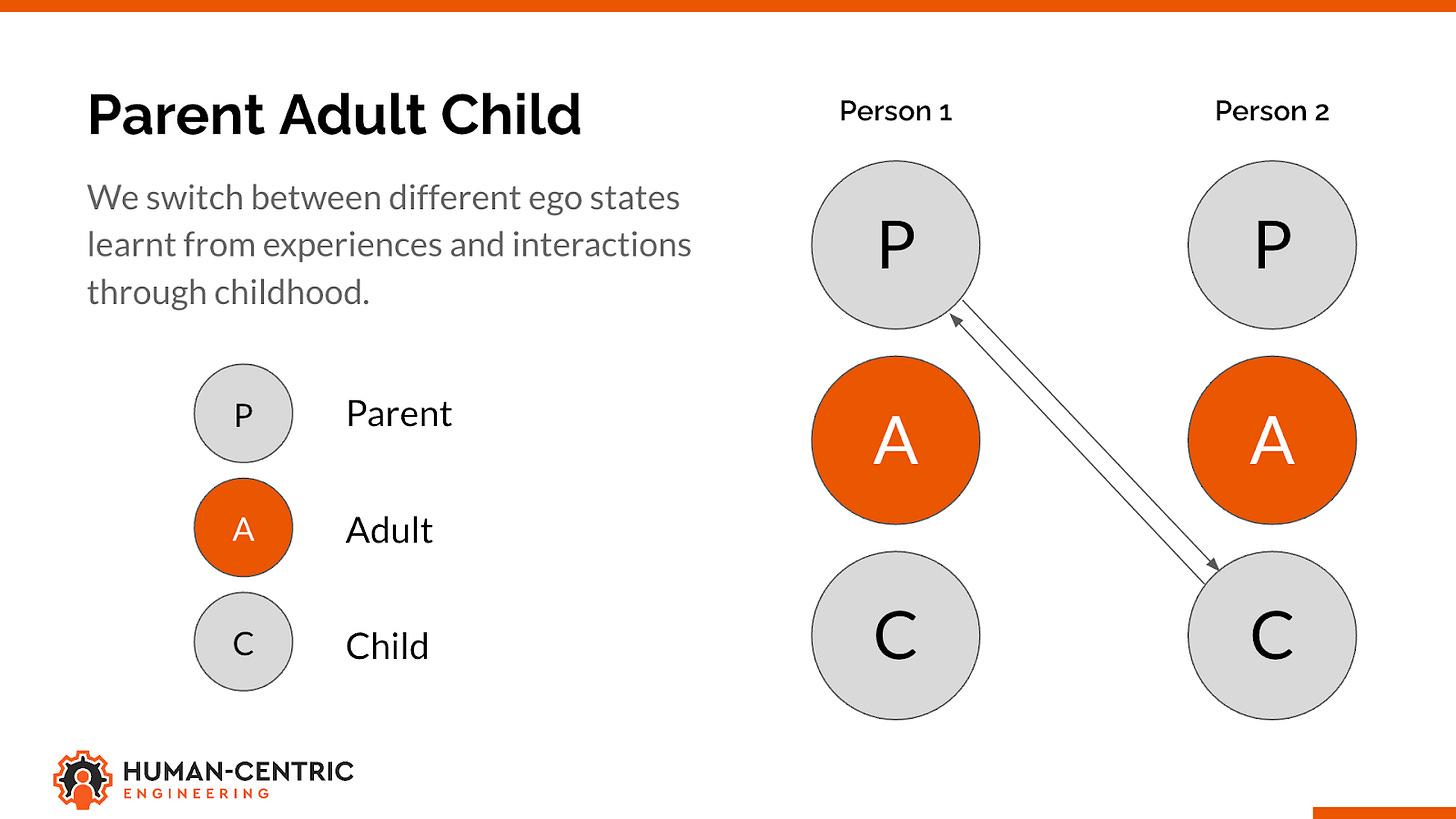

The Parent-Adult-Child model

The Parent-Adult-Child model describes different ego states we adopt in our interactions, based on our observations and experiences during childhood.

The Parent ego state embodies internalised messages and attitudes from our caregivers and authority figures, including the Nurturing Parent as well as the Critical Parent to express support or judgement. A manager praising an employee reflects the Nurturing Parent, while criticism from a Product Manager may stem from the Critical Parent.

The Adult ego state represents rational, reasoned and objective thinking based on the available information. It is involved in the logical decision-making we aspire to as engineers. Transactions taking place on an Adult-to-Adult basis are constructive and in good faith, as they involve exchanging neutral strokes necessary for collaborative problem-solving.

The Child ego state captures emotions and behaviours from childhood, encompassing both spontaneous creativity as well as compliant or rebellious reactions. There are two Child types, the Natural Child and the Adapted Child. The Natural Child can manifest as technical innovation or uninhibited convivial banter between colleagues. The Adapted Child can either be expressed as compliant and obedient validation-seeking people-pleaser or as rebellious in the face of authority or in response to criticism.

Complementary transactions occur when the addressed ego state responds appropriately, while crossed transactions lead to misunderstandings and conflicts. A crossed transaction occurs when there is a misalignment between Person 1's intended ego state and Person 2's responding ego state.

Examples of crossed-transactions are where:

An Adult-to-Adult stimulus from Person 1 is met with a Parent-to-Child or Child-to-Parent response from Person 2.

A Parent-to-Child stimulus being met with an Adult-to-Adult response

Recognising these patterns helps us to identify which ego state we are operating from, giving us the option to deliberately change our ego state. If a colleague is talking to us from the Critical Parent ego state we can respond automatically as a Rebellious Child or we can choose to diffuse the situation by responding as an Adult, with the hope of bringing the interaction back to an Adult-to-Adult transaction.

Engineering games

Author Kurt Vonnegut describes the book Games People Play as “A brilliant, amusing and clear catalogue of the psychological theatricals that human beings play over and over again”

Games are social transactions which follow predictable patterns, deviating from Adult-to-Adult interactions into Parent and Child ego states.

We play games partly to protect ourselves from the vulnerability required for actual intimacy. Intimacy in the work setting is being truthful with one another. Whether conveying our concerns, asserting a viewpoint or admitting to a weakness, workplace intimacy requires a level of vulnerability to take a social risk. Intimacy is difficult at work because there’s often an underlying feeling that we’re always being judged - we want to appear to be smart and productive to get that bonus, pay rise, or promotion. Much of our behaviour is performative as we indulge in impression management, working to ensure others have a positive view of us. We try to look busy and useful. So the workplace is an ideal theatre for the drama of our game-playing - and supposedly ‘rational, logical, and emotionally detached’ software engineers are just as prone to game-playing as anyone else.

What do engineering games look like? Here are a few examples, drawing from the catalogue of games in the ‘Games People Play’ vernacular and applying them to software teams.

“See What You Made Me Do”

An engineer is working on a complex task that requires deep focus. When a teammate interrupts to ask for advice or get input on an issue, the engineer reacts abruptly, expressing frustration and emphasising how this interruption will “cost hours of productivity” and “set back the entire project”. With a self-righteous and resentful attitude, they secretly enjoy the opportunity to shift responsibility for any delays onto the teammate who interrupted them.

The interrupted engineer adopts a victim role from the Adapted Child ego state, acting as though they are powerless to manage interruptions or negotiate boundary setting while exaggerating the impact of the disruption. They may also flip to the Critical Parent ego state, chastising their teammate, implying that their colleagues should have known better than to interrupt. This way, their attitude comes to dominate the team dynamics, the engineer has displaced accountability and elevated their status as the virtuous engineer.

“Now I’ve Got You, You Son of a B****”

A Tech Lead establishes highly specific coding standards, architectural expectations, or performance metrics that are difficult to meet given the team’s resources or constraints. The team feels they have to agree to stringent expectations. Instead of offering support or clarifying these standards, the Tech Lead watches and waits for mistakes to be made.

The Tech Lead gets to play the Critical Parent role, feeling superior when the standards are transgressed due to a tiny ‘gotcha’ which they use to aggressively reinforce their authority. They become the ultimate arbiter, deciding who is "good enough" to meet these standards, reinforcing their self-image as the "only competent person" on the team. The team becomes defensive and risk-averse.

“Kick Me”

The "Kick Me" game is a self-sabotaging behaviour pattern where an engineer unconsciously invites criticism or blame. It might play out when engineers set themselves up for failure or invite negative feedback by repeatedly taking on too much work, underperforming, or failing to ask for help - ultimately inviting a “kick” from their colleagues or a reprimand from a manager. The engineer may then react with resentment or frustration, reinforcing a pattern of feeling unfairly treated or picked on.

In “Kick Me” the engineer imbues a victim consciousness, a needy Child state, unwittingly setting up scenarios to gain sympathy or support. Instead of asking directly, they create indirect signals, making their struggles highly visible so that they’ll force others into the Nurturing Parent role of the Rescuer, reinforcing the engineer’s passive dependence on others and perpetuating the cycle of drama.

“Why Don't You... Yes, But”

This game sees an engineer seeking advice around a problem, only to reject each suggestion with a "Yes, but..." response to every potential solution offered by colleagues. The engineer playing this game maintains a sense of being “stuck” or under-resourced while deflecting responsibility for solving the problem. Colleagues come in as Parental Rescuers, suggesting solutions like breaking down tasks, whiteboard, asking for additional resources, pair programming, or adopting a different approach … but the engineer always has an excuse as to why this won’t work. The engineer maintains their image of being unsupported, while the rest of the team becomes exasperated.

The engineer operates from the Adapted Child ego state, maintaining a sense of helplessness while seeking sympathy and validation by focusing on what’s going wrong and why nothing seems to help. This position allows them to avoid taking ownership of finding a solution while feeding their need for continued attention.

“Harried”

The "Harried" game player constantly claims to be overwhelmed or "snowed under" with work, using their ‘busyness’ as a shield against taking further responsibility, making decisions, or receiving feedback. This game might see a manager lamenting how overworked they are, with a back-to-back diary while simultaneously refusing to give others the opportunity to help.

The manager is always “too busy” to address pressing issues and continually cancels their 1:1s because something more urgent has come up. Despite this, they may take on tasks that reinforce their busyness, like firefighting issues or micromanaging others, which they then use to strengthen their narrative of being overwhelmed. Long-term strategic issues and concerns of the team are avoided because the manager has so little time to deal with them.

The harried manager operates from an Adapted Child ego state, projecting a sense of helplessness or powerlessness in the face of their workload. They are positioning themselves as a Victim of circumstance, claiming that they have no control over their “never-ending” workload. In claiming to be continually swamped, they deflect responsibility for any gaps or mistakes in their work. They then try to justify incomplete tasks or delays by pointing to their workload, allowing them to avoid accountability for outcomes. They also enjoy the implied status of being indispensable, maintaining their self-image as someone crucial to the team. The harried manager protects themselves by keeping others at a safe distance.

“Greenhouse”

This one will resonate well with engineers. “Greenhouse” was a game described by Eric Berne which these days we would call the “Toxic Positivity” game.

Greenhouse involves creating an overly safe and supportive environment where negative feedback or genuine concerns are avoided. This could involve a manager or team who insists on keeping everything upbeat and "positive", a world of sugar-coated rainbows and unicorns. This makes for a stifling atmosphere where team members feel they can’t express legitimate frustrations, give critical feedback, or expose important realities. We end up with an artificial harmony that undermines honest communication.

“Look Ma No Hands”

The ‘Rockstar Engineer’ who always wants to be the ‘go-to’ person for complex tasks is playing "Look Ma, No Hands" attempting to show off by taking risks or completing tasks without help, seeking admiration or attention from others. They are indulging their Natural Child ego state taking on high-visibility challenging tasks with little collaboration, proving they are the indispensable hero of the team. Their work is undocumented and there is no knowledge sharing to preserve their irreplaceability.

Others in the team have missed out on the learning opportunity but the ‘hero’ has had the thrills of achievement and avoided the vulnerability and trust needed in effective collaboration.

The games I’ve tended to play

It would be remiss of me to sneer at people playing games without taking a moment to look back at my own behaviours through the lens of games. I felt uncomfortable, and slightly ashamed, thinking about my own game playing, but I shouldn’t be - this is what it is like to be human. We learn to play games to get what we need, and game-playing is part of the social drama that creates the stories of our lives. We’re not robots.

So What game-playing have I indulged in?

“Wooden Leg”

Well, if I’m honest, I’ve played Wooden Leg in a few ways. Wooden Leg is where we play on some kind of disadvantage, whether real or imagined, to excuse a lack of effort or avoid responsibility. I’ve played on the disadvantage of social mobility “I’m just a working-class bloke from Lowestoft” has been a good Wooden Leg to lean on, to avoid social awkwardness around associating with more ‘well-to-do’ people.

I’ve also used my lack of a Computer Science degree to avoid certain technical aspects of engineering, especially around enterprise system design and higher-level architecting - I’ve sometimes avoided delving into these areas too deeply with the excuse that “I’m just a web app guy”.

“I’m Only Trying to Help You”

When I was in my 20s, I would often default to trying to play the ‘hero’ in social situations - perhaps trying to ‘fix’ people with health or well-being advice, possibly playing the ‘Psychiatry’ game as described by Eric Berne - offering a misplaced amateur diagnosis to a friend after reading the latest pop-psychology book. I would feel virtuous and heroic but in reality, I was operating from a Parent ego state, seeking control and superiority, forcing the other player into their Child ego state while avoiding my own issues. Perhaps by writing articles like this, I’m still falling into the Psychiatry game?

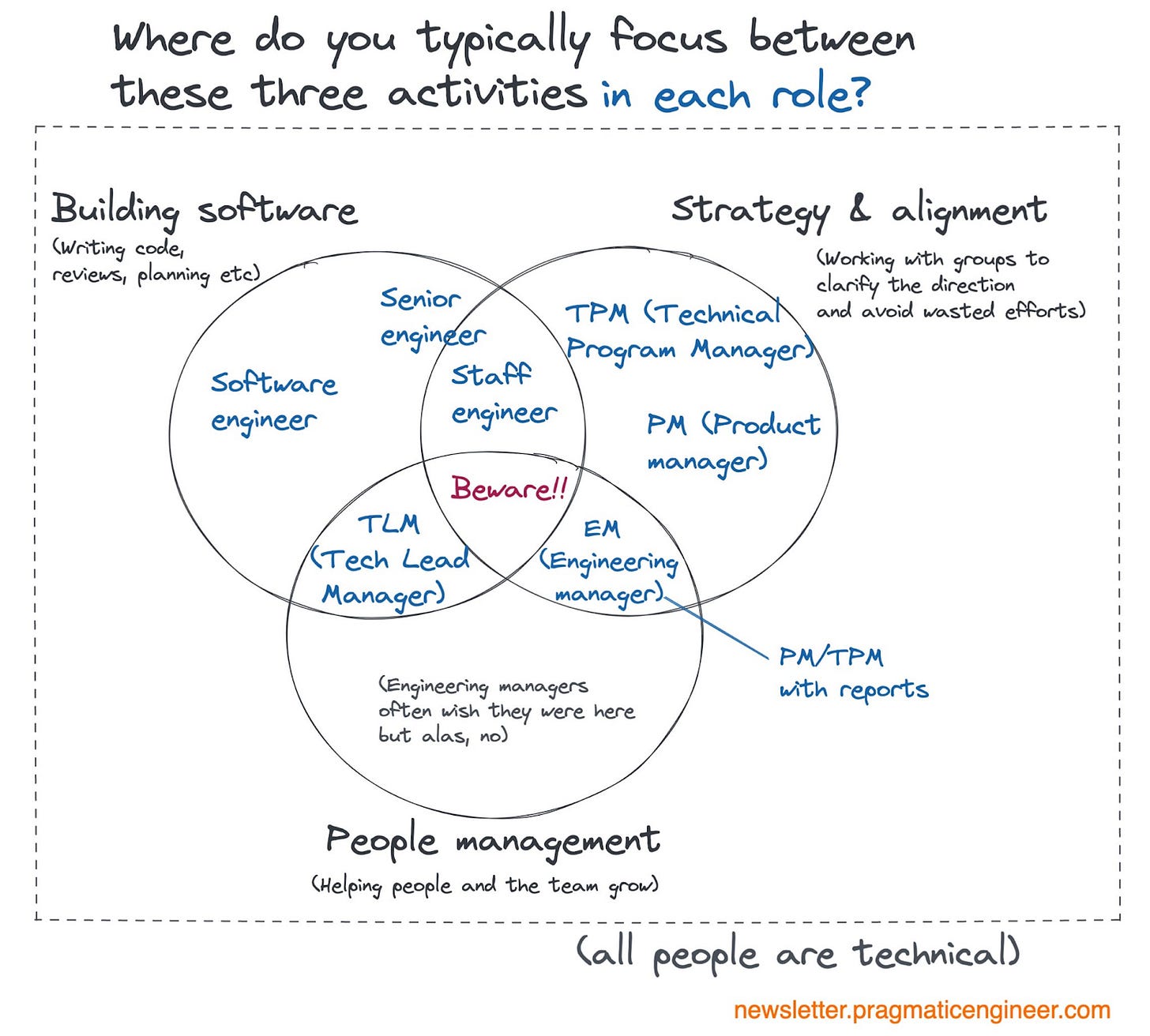

One way that I fell into the I’m Only Trying To Help You game came up when I initially entered Engineering Management. Instead of playing to my strengths by focusing on people management and aligning the team around the organisational strategy I clung on to a few engineering responsibilities which would have been better handled by the team. For almost a couple of years, I carried on acting as a release engineer, prepping the release, dealing with merge conflicts, and deploying to production once a fortnight at 4 am in the morning.

I wanted to keep my technical relevancy for the team, I wanted to help, but I could have helped more by letting go, passing on the reins to others, leaving more time to focus on people management and strategy & alignment. By keeping on-hands technically I was spreading myself too thinly, as described in Gergely Orosz’ diagram in his The Pragmatic Engineer Substack

We’re all gamers

The point of this article isn’t to take a cheap shot at people who become embroiled in the social drama of game playing, because playing social games is something we all do, a natural human behaviour that we use to navigate complex social dynamics. Looking at our interactions through the lens of games may highlight some patterns we unconsciously fall into, adopting Child or Parent ego states. Being aware of these ego states may help us realise they are unhelpful in certain situations, and that striving for Adult-to-Adult interactions may pave a more productive way forward.

Once we get beyond game playing we find the intimacy we often crave. Relating to one another authentically in good faith, without feeling the need to be on guard against ulterior motives.

“For certain fortunate people there is something which transcends all classifications of behaviour, and that is awareness; something which rises above the programming of the past, and that is spontaneity; and something that is more rewarding than games, and that is intimacy.”

- Eric Berne, Games People Play

At Human-Centric Engineering we are offering an entertaining workshop to explore the games that emerge in software engineering environments to help teams open up around the dynamics of their relationships - a light-hearted way to reflect on team dynamics and find better ways of working. See Games Engineers Play Workshop for details.

Loved this one, John - Games We Play was a new framework for me! Thank you for writing such in-depth pieces on useful dimensions of work!

Such a great and unique insight. Kudos. The concepts seemed a bit esoteric at first but the ‘Games People Play’ as engineering examples really made it all tangible. Well done. Such a great idea for a workshop too.!