Emergence, and Team Dynamics

How understanding the concept of emergence helps when leading teams

It’s rare to hear the idea of ‘emergence’ mentioned in relation to team management, even though teams of people are a ‘complex adaptive system’. This article explores how understanding the concept of emergence can inform our approach to leadership and team dynamics.

This article is born of frustration. In previous engineering leadership roles, I occasionally encountered resistance when advocating for more nuanced approaches to leadership. While I emphasised creating conditions for desired team dynamics to emerge organically, I often faced pressure to adopt more forceful, interventionist approaches. Despite protesting that ‘You can’t make grass grow quicker by pulling on it’, I would sometimes be pressured into ‘ass-kicking’ actions to accelerate projects and ‘motivate’ engineers, disregarding the delicate nuances of cultivating autonomous self-organising teams. Perhaps my inability to articulate some of my nuanced ideas was the problem. Hence this article.

Interestingly, however, when talking to software engineers directly, they would resonate with the subtleties of management and leadership concepts that I enjoyed bringing up in conversation. With a natural curiosity and desire for understanding, they seemed to embrace conversations about ‘complexity’ and ‘emergence’.

In the following sections, I'll delve into the nature of emergence, its relevance to team dynamics, and how embracing this concept can aid actions which lead to more effective, productive, and humane teams. By understanding teams as complex adaptive systems, we can move beyond simplistic management techniques and foster environments where collective intelligence and innovation can flourish.

What is emergence?

Although the idea of emergence is a relatively modern concept from the fields of chaos theory, complexity science and systems thinking, it does have some roots in ancient thinking.

The phrase "the whole is greater than the sum of its parts" is often attributed to Aristotle, and though he didn't use those exact words, he did express related ideas. In this article, I will explore the idea that a team of people is a complex adaptive system, where the team as a whole has a quality that is distinct and that the collective intelligence and behaviours of a team exhibit the qualities of emergence - something novel that couldn’t be described or predicted by looking at the individual components of the team (the people).

We see emergence in nature. Think of the snowflake. Every snowflake is a unique form, a geometric pattern that emerges from certain atmospheric conditions. Despite starting from similar initial conditions, no two snowflakes are exactly alike. The final shape of a snowflake cannot be predicted solely by examining its starting components or the basic rules of ice crystal formation. The snowflake has a kind of emergent intelligence of its own. Snowflakes exhibit self-organisation as they grow. The six arms of a snowflake develop independently yet maintain remarkable symmetry due to their shared microenvironment. The elaborate structures of snowflakes emerge from countless molecular interactions at the microscopic level. This demonstrates how simple rules at a small scale can lead to complex patterns at a larger, macroscopic scale.

Ant colonies are another example of emergence in nature, demonstrating how complex, collective behaviours can arise from simple interactions between individual ants. Collective intelligence, problem-solving abilities, and sophisticated social structures emerge from the simple actions and interactions of individual ants. Through self-organisation, these colonies exhibit division of labour, efficient resource management, and adaptive responses to environmental changes, all without any single ant needing to understand the big picture. The resulting colony-level behaviours and structures are far more complex and intelligent than what any individual ant could achieve, demonstrating the emergent properties of complex adaptive systems and how emergence leads to outcomes that are greater than the sum of their parts.

Emergence in human systems

This principle of emergence extends beyond snowflakes and ant colonies and can be observed in various natural and artificial systems. It is particularly relevant to the dynamics of human societies and economies. Think about the emergent patterns of trading in financial markets, how the ‘price’ of something is determined by many human preferences and interactions as per Adam Smith’s description of the ‘invisible hand’. Human society, organisations, and teams all exhibit the properties of emergence, so it’s worth digging into the concept to bring subtleties to our understanding of the behaviours and interactions in the teams we are managing or working in and how we might be able to create the best conditions for the emergence of a desirable team dynamics.

So, the idea of emergence is a fundamental concept in complex systems theory that describes how novel properties, patterns, or behaviours arise from the interactions of simpler components. This phenomenon occurs when the collective behaviour of a system exhibits characteristics that are not present in, or predictable from, its individual parts.

At its core, emergence refers to the formation of collective behaviours - what parts of a system do together that they would not do alone. This concept challenges reductionist approaches (common in management thinking and practices) by asserting that the whole is often more than simply the sum of its parts. Emergent properties cannot be fully understood or predicted by analysing the system's components in isolation. We do not understand the collective potency of a team through individual yearly performance reviews.

One of the key characteristics of emergent phenomena is that they tend to occur at a macro level, arising from micro-level components and processes. This scale difference helps our understanding of how simple interactions can lead to complex, often unexpected outcomes at a higher level of organisation.

Seeing teams of people as complex adaptive systems helps us to realise why certain actions and interventions might have unintended consequences, rippling through the system to create second-order effects that we could not have predicted. Asking a software engineer to drop what they’re doing in order to address a more urgent problem that has been raised by the CTO will have consequences that we cannot predict in advance.

Teams as complex adaptive systems

Teams can be viewed as complex adaptive systems with the following key characteristics:

Self-organisation: Teams develop behaviour patterns and ways of working without external direction.

Non-linearity: Team outcomes are not simply the sum of individual contributions.

Adaptability: Teams evolve and respond to changes in their environment - the team can act and learn as an organisational sensing organ.

Open systems: Teams interact with and are influenced by their broader organisational context.

A team develops its own character and intelligence over time. This will include organically adopting practices which work for the team, and discarding those that don’t. It’s important that the team are encouraged to experiment with their own approaches to managing their ever-changing environment, an exercise in continual learning and adaptation.

Emergent properties in teams

Several important team attributes emerge through member interactions:

Group identity

Group potency (a collective belief in team effectiveness)

Team cohesion

Shared mental models (team cognition)

A collective memory (Transactive Memory System)

Team norms and culture

Leadership dynamics within the team

A team’s shared understanding of their domain emerges over time, becoming a collective mental model or ‘team cognition’ used to address challenges through their cohesive ways of working. A team narrative emerges from people’s interactions and natural leaders can emerge within the team, according to the problems at hand.

The unpredictability of emergence

It's important to note that emergent team properties cannot be precisely engineered or predicted:

Simply assembling skilled individuals does not guarantee an effective team.

Rigidly structuring teams may stifle the natural emergence of beneficial dynamics.

Team performance often exceeds or falls short of what individual capabilities would suggest.

A team of ‘averagely skilled’ people working collaboratively can outperform a team of ‘rock stars’ who struggle to collaborate. Team dynamics are as crucial to performance as individual skills but we never know precisely what will emerge from the team chemistry. This is a good reason to be really careful of re-orgs and moving teams around. People are not interchangeable cogs, even if they have the same title and skills on paper.

Creating conditions for the emergence of desired team dynamics

While emergence can't be controlled directly, leaders can foster conditions that promote desirable team dynamics:

Establish a clear collective team purpose and goals.

Encourage open communication and psychological safety.

Allow time for team members to interact and build relationships.

Provide opportunities for collaborative problem-solving.

Ensure an efficient flow of information with optimal feedback loops.

Balance team composition in terms of skills and personalities.

Remember that no single leader creates an ecosystem - it is a participatory process of co-creation.

In nature, it is clear that the ecosystem dictates the thriving of plant and animal life. Think of fish struggling for their survival in a polluted river. Human teams need a nourishing environment of collaborative ease, trust, social harmony and open dialogue. A team needs structures, processes, and a team charter that enables flow.

Monitoring and guiding emergence

Leaders should:

Observe emerging team patterns without overly interfering.

Think about how to create the right conditions for team functioning.

Gently nudge, guide, and support when needed.

Ensure that autonomous teams have the right balance of competencies and the right information upon which to act.

Remember that leadership is an emergent phenomenon, anyone can lead according to their competencies and the needs of the given situation.

Follow David Marquet’s advice from ‘Turn the Ship Around’ so that instead of bubbling up information so those in authority can make decisions, we should “Move the authority to where the information is” - to the autonomous, self-organising team.

A facilitative leadership style is key to nurturing the conditions for the natural emergence of cohesive behaviours and interactions. Be a gardener, rather than a micromanaging chess master. The leader is a catalyst for emergence.

The emergence of team dysfunction

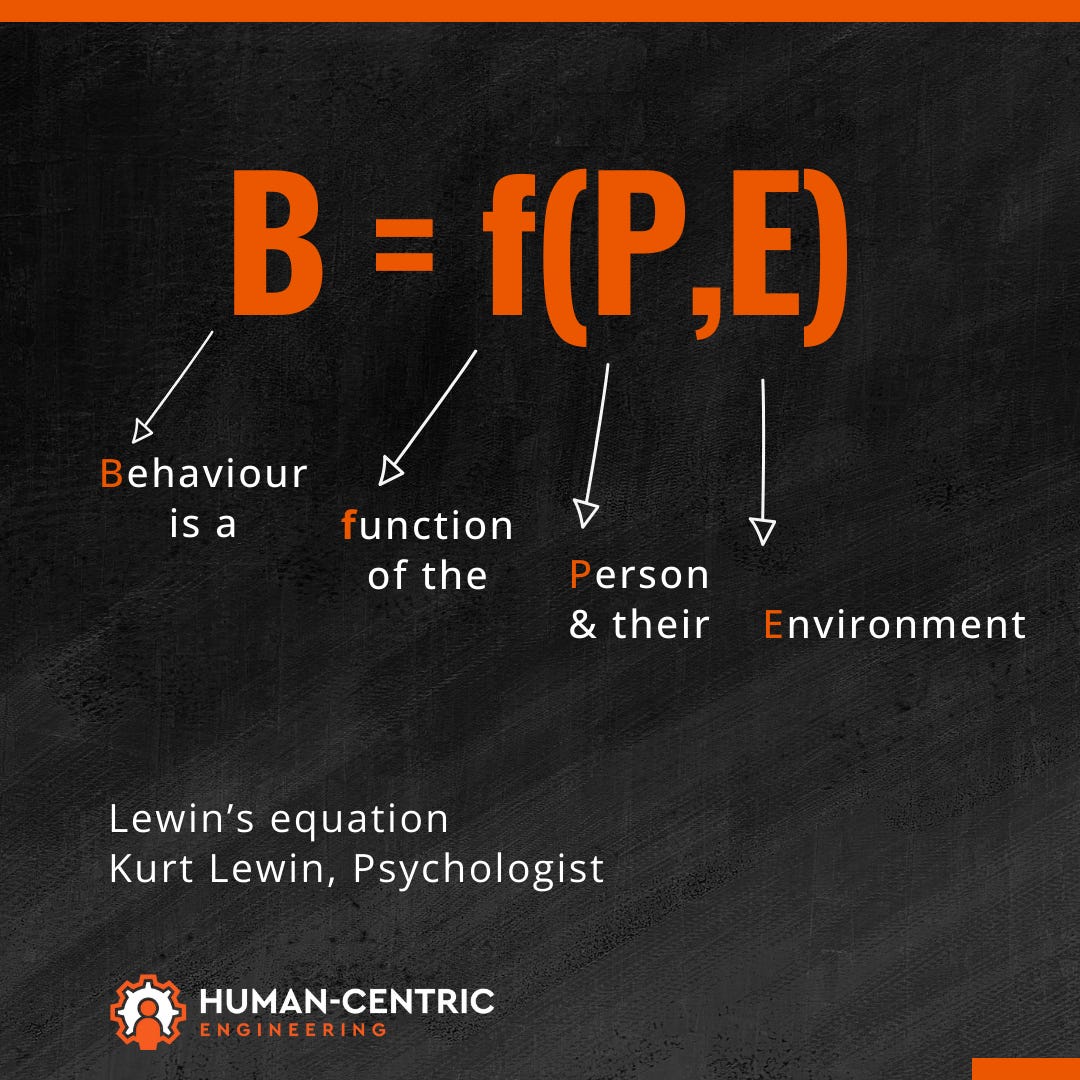

Emergence is a phenomenon of complex adaptive systems, and if the conditions are toxic, or anti-human, we’ll likely see the emergence of team dysfunction. B = f(P, E) - Behaviour is a function of the Person and their Environment as psychologist Kurt Lewin said. When fear is the prevailing organisational operating system, when blame is common, when messengers are shot, when power dynamics, status jockeying and political manoeuvring reign, and when responsibilities are shirked when information doesn’t flow when trust is low and gossip is high - the conditions of the ecosystem will likely cause the emergence of dysfunction.

Sadly, and especially during the current economic downturn that has seen so many layoffs in tech, the conditions are not ideal for the emergence of highly functional team dynamics.

“Where people thrive, organizations prosper” - John Morley

Proactively managing for emergence

I am not urging for passivity in management, where leaders should sit around and wait for the right ‘emergence’ to happen. But I am highlighting the benefits of more contemplative management, for an appreciation of the subtleties at play in team dynamics.

‘Now emergence will happen anyway, but there is no reason why we shouldn’t give it a helping hand or two. But the single most important aspect of management here is to have the right sensor networks in place to detect the early signs of emergence so that you can push more energy in the direction of patterns that appear to be beneficial and shift it away from others.’

- Dave Snowden, Managing for emergence through abduction.

Often managers have a bias to action, to intervene, to push things along. The worst kind of management is seagull management, where a manager only arrives on the scene when there’s a problem to deal with, they fly in, flap and squawk, dumping on everyone from a great height, only to fly off and leaving others to deal with the consequences. This is short-term thinking and a short-term management style.

The more contemplative manager will seek to help create the right conditions for a team to thrive and for the desired team dynamics to emerge. They will:

focus on ensuring that the team's purpose and goals are clearly defined

create team structures that are conducive to humane working conditions (see Team Topologies)

look not just at the performance of individuals, but at the quality of their relationships and interactions

facilitate opportunities for Team Reflexivity (a deliberate process where the team reflects on its goals, strategies, decision-making processes, and overall functioning)

survey the team to understand the Team Culture

guide, enable, and support

In other words, they will not be passive, but very proactive in creating the conditions for emergence. This doesn’t happen by copying team structures that worked at Spotify, or imposing the latest cookie-cut methodology - but through supporting the organic evolution of self-organising, self-determined teams in conditions that nurture and nourish relationships.

‘We assume that “the team” is something that behaves differently from a mere collection of individuals, and that the team should be nurtured and supported in its evolution and operation’

Matthew Skelton & Manuel Pais, Team Topologies

Understanding teams as complex adaptive systems with emergent properties allows leaders to move beyond simplistic, mechanistic views of team building. By creating the right conditions and skillfully guiding emergence, organisations can cultivate high-performing teams that are more than the sum of their parts. Discussing the idea of ‘emergence’ in teams helps us to think more clearly about creating the conditions for effective team dynamics.

Next time I’m struggling to articulate the properties of emergence in team dynamics, I’ll hopefully be able to bring clarity by referring them here. Thanks for reading and keen to hear your thoughts.

It is often Engineers who understand best these concepts. Traditional management education is still grounded in traditional scientific management from closed systems. Engineering is much more comfortable with dynamical systems theories.

If you are interested, Lewin directly and indirectly inspired a whole breakaway of cognitive science, Ecological Psychology. This unlike traditional cognitive psychology looks to understand the forces at play in the “E” part of Lewins equation whilst not removing the dynamical coupling with “P”.

This ecological approach even challenges the underpinnings of cognition

https://davehodges.substack.com/p/challenging-the-cognitive-status