Changing my mind on whether managers should keep coding

Not just to advise and mentor technically, it’s so they continue to have empathy

It’s often worth challenging your beliefs and values - ideas only evolve when they are challenged. Some of our beliefs are a post-hoc rationalisation, where we come to believe something after the fact to explain our actions in a way that aligns with our self-image or desired narrative.

I was never the most talented software engineer. I’ve created a good few web applications end-to-end by cobbling things together but I tend to apply the Pareto Principle to coding: I can get 80% of the job done by knowing 20% of what there is to know, and that has served me reasonably well. When I went into managerial roles I was pleased to be no longer ‘hands-on’ as it meant I could let go of the insecurities of comparing myself with better developers.

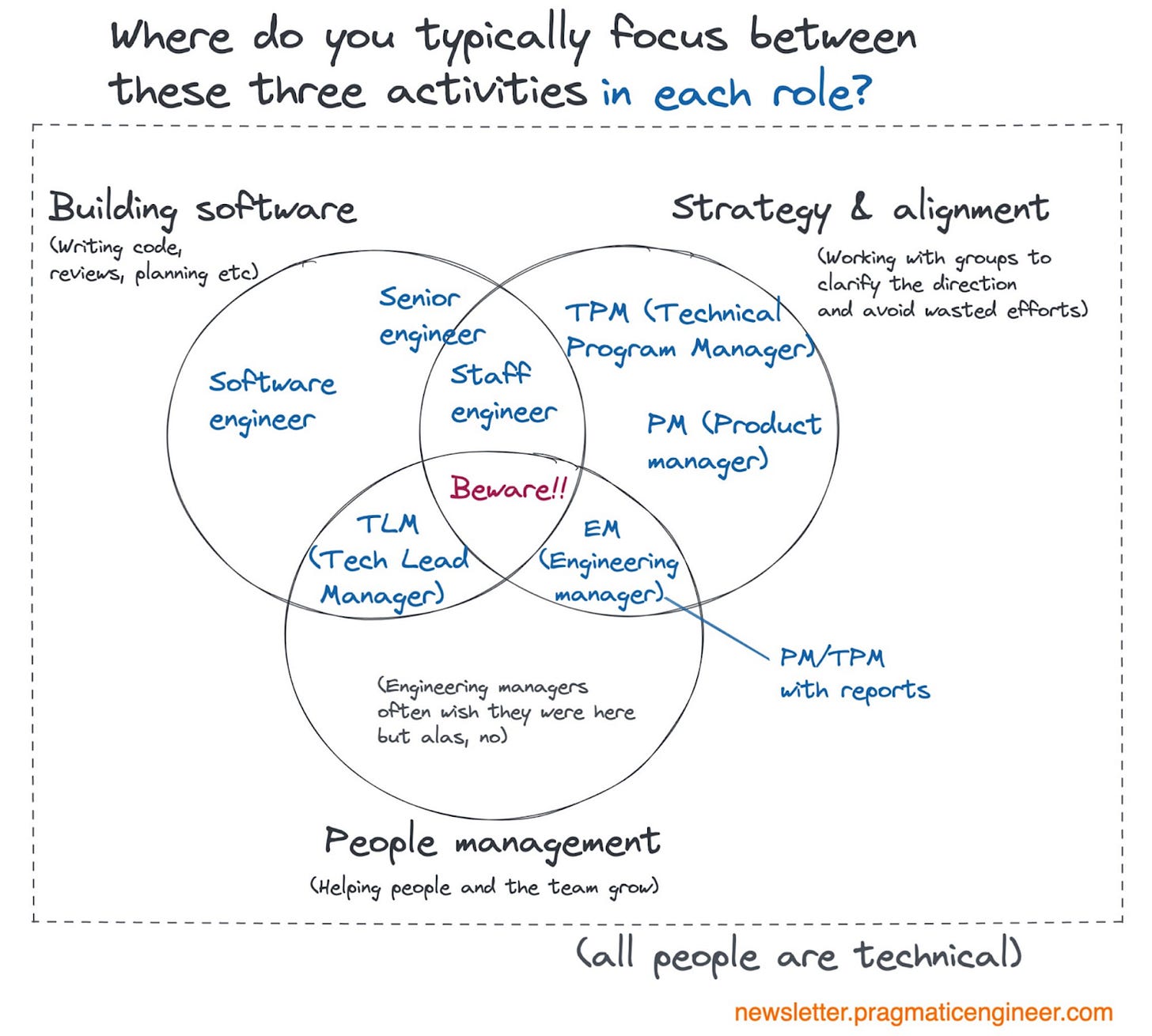

My letting go of being ‘hands-on’ may have turned into the post-hoc rationalisation that ‘Engineering Managers should not be coding’. Confirmation bias would harden this belief, especially when stumbling upon articles that laid it out for me with a supporting Venn Diagram (from Gergely Orosz in his The Pragmatic Engineer Substack):

So I’ve been asserting my view that engineering managers shouldn’t be hands-on because managing people and achieving strategic alignment are sufficiently demanding in their own right and should consume the manager’s time and attention. An engineering manager should be working to create the conditions to enable Individual Contributors to make their deepest contributions. By stepping away from building the software, they are handing over responsibility to their teams, who through the psychological mechanism of the Pygmalion Effect, will likely rise to the expectations placed upon them.

It was so easy for me to let go of coding. I never considered myself a talented engineer, my identity wasn’t attached to my coding competencies, so it was more of a relief for me to let go. There were many aspects to building software that I enjoyed, especially the thrill of bringing a creative idea into existence - the magic of seeing something on the screen that originated as a random insight in your mind. But there were other things I cared about more and which held more fascination for me, particularly trying to understand human psychology and the complexities of our social relationships. So, for me, managing people was a more interesting challenge.

If, however, I had been a much stronger software engineer, with years of investment in my learning, and perhaps even hailed as an expert by my peers, then letting go of that identity, and the many years of applied study in engineering practices, would have been so much harder. It wouldn’t have been hard to create my own post-hoc rationalisations about the importance of maintaining a hands-on approach, guiding and mentoring the team and applying my engineering discernment in code reviews and architectural decisions. We form beliefs that confirm and validate our behaviours, preferences, and prejudices, thus avoiding the painful cognitive dissonance where our actions are misaligned with our values.

I was chatting about this with my colleague,

, who as a published author of technical books reached a higher technical level than me. Simon said that the temptation to stay hands-on in the same way as before whilst managing the team was very strong, “I was burning out - and not doing a very good job of managing - until I stepped right back and stopped coding entirely.”Changing my mind

I’ve adjusted my stance after returning to coding after a 4-year exodus from any IDE. In doing so, I’m rediscovering many of the joys and sorrows of the practice of software engineering. Simon and I are currently building a platform to make it easier for people to engage with the services we offer. The platform will host the various surveys we use to gain insights into an organisation's engineering culture as well as our approach to helping engineering leaders reflect on their leadership capabilities. The initial MVP offering will be a daily survey for software engineers, 3 questions to hear the engineering voice across the industry.

The engineering landscape has changed somewhat since I last built anything. Previously I would be using the LAMP stack (Linux, Apache, MySQL and PHP) along with VueJS on the front end. Nowadays this stack has faded in popularity and there are many more choices available. We’ve decided to use Node for the backend with AWS to provide cloud services and NextJS/React for the front end, with an integration to Slack. And of course, one other major change has been the arrival of AI coding assistants, a real game-changer when it comes to learning some of these technologies I’m less familiar with.

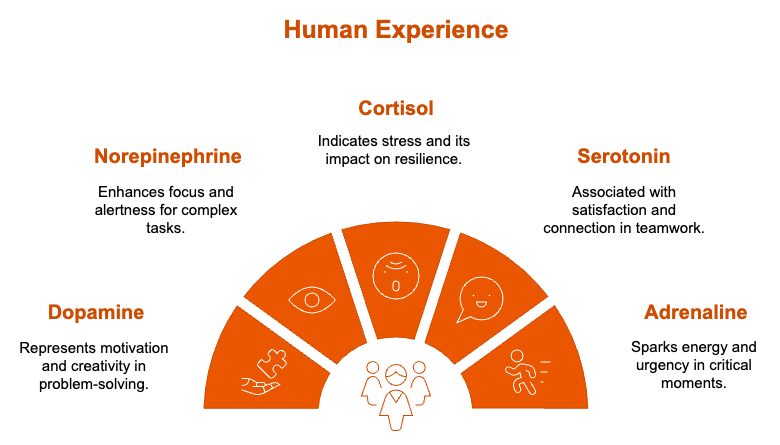

Even with the easy availability of this fancy tech, and with AI assistance, the felt pride in getting something to work and the despairing struggles when you’ve made the wrong architectural choices remain. There is no getting away from the rollercoaster of highs and lows that you feel when wrangling code into a working application. The moment you’ve solved one problem, you’re back in the thick of it with something else that stretches your limits and tests your patience. A cocktail of hormones and neurochemicals ebb and flow through your body like the tides of the sea.

The ebb and flow of neurochemistry

Dopamine flows as you work through a complex problem, part of the reward system inspiring your persistence and creativity. When the solution clicks into place, you feel a brief but enjoyable high which sets up your motivation for more of the same.

Norepinephrine plays a significant role in problem-solving by enhancing alertness and focus, helping you to maintain concentration during complex tasks. It helps in filtering out distractions and boosts memory formation, which is crucial for applying past knowledge to current challenges.

But when you're staring at a blank screen, paralysed by indecision, feeling the pressure of knowing that you’re not going to complete this task as quickly as you estimated, your cortisol levels rise, the stress hormone which sharpens your focus but gnaws at your resilience, sending you to the kitchen for a chocolate fix.

Collaborative success in an aligned team heightens the presence of serotonin as solutions emerge through collective genius, bringing feelings of connection and satisfaction. A high-five with a teammate or receiving encouraging feedback from close colleagues may be accompanied with the release of oxytocin, subtly reinforcing bonds and belonging.

And of course, adrenaline kicks in during critical moments that typify engineering - tight deadlines or last-minute production failures, sparking energy and creating a sense of urgency, but leaving you drained if it lingers too long.

These fancy scientific concepts and names are interesting, but they are not the human experience. The human experience is more than the individual biological processes going on under the skin, it's the entirety of human consciousness, the integral whole. No matter who we are, we all experience the vicissitudes of life. Even the most stoic, rational, and accomplished software engineer will experience these ups and downs, although we all have different configurations - our unique settings for joy, and unique tolerance windows to life’s stressors.

Since we’re all at the mercy of life’s emotional rollercoaster, we can put ourselves in other people’s shoes, we can empathise with one another, and it’s this ability that helps to build trust, to see another person and relate to their needs, realising that we are tethered to each other by the shared energies expressed through our emotions. By continuing to code as a manager you’re maintaining your ability to empathise with other engineers - you are creating deeper bonds with your team which could be more important than technical mentoring and guiding. A manager’s ability to relate to the work undertaken by the team is key to gaining people’s support and trust in the direction you are taking for the team.

Empathy in engineering

Empathy in software engineering goes far beyond understanding the struggles of debugging or the momentary thrill of shipping a feature. It’s about truly seeing and valuing the human beings behind the keyboards - their aspirations, frustrations, and the unique contributions they bring.

One important aspect of empathy is understanding the mental load of problem-solving. Software engineers constantly juggle competing priorities, context-switching between tasks, and holding a detailed appreciation of the problem in their minds. A manager who continues to code stays connected to the mental effort and patience required and the satisfaction of small but meaningful victories. Simply acknowledging the complexity of the work reassures an engineer that they are understood and supported.

Empathy also involves recognising the diversity of emotional experiences within a team. Some engineers thrive under pressure, while others might struggle with imposter syndrome or burnout. A manager who empathises with these differences can tailor their approach, offering encouragement, constructive feedback, or opportunities for growth in ways that resonate with each individual. It’s not about trying to understand the situational context of each person - their unique human needs and circumstances.

Software teams are often at the intersection of competing stakeholder demands, technical constraints, and shifting priorities. Managers need to empathise with people feeling these pressures, helping bridge the gap between technical and non-technical stakeholders. By empathising with the perspectives, goals and scope of multiple stakeholder groups, they can act as effective translators and advocates, ensuring alignment without compromising the team’s well-being.

Understanding cognitive load

Recognising emotional diversity

Bridging stakeholder gaps

Being present and engaged

Sincere self-awareness in social situations

Empathy involves being present, engaged, and being shoulder-to-shoulder with the team members. Good leadership means being believable, if your team believes in your sincerity, and your authentic support for them, they will reciprocate your trust in them and it’s all built upon genuine empathy, an honest intention to understand and relate to another person’s experiences.

Empathy is frequently dismissed as ‘fluffy’. It’s not a capability we can easily measure, not a competency that can be proved in the way we can demonstrate our technical prowess. But it is a capability that develops slowly, through interactions with others and sincere reflection on our own emotional involvement in the interactions. It’s a lifelong practice, invaluable in its rewards.

Should managers keep on coding? Well, ‘it depends…’ - there are always situational trade-offs to consider, but experiencing the emotional rollercoaster of working with code again has certainly reminded me of the everyday realities of what it is like to be a software engineer.

Yes but...managers should keep coding in order to maintain an interest in what their reports are working on and in order to empathize, but the manager doesn't need to be working on the same project side-by-side with their team. If you think the answer is to roll up your sleeves and get into the trenches with them, you'll likely get in their way, unconsciously start micromanaging the project or asserting too many of your own biases which could be detrimental to team morale and individual autonomy. You also won't be very accessible to team members as a leader or coach because you won't be able to provide that elevated view of the team and the work that only comes from stepping back.

Finally I'll say this: tech has an over abundance of managers who are so obsessed with being the smartest 10x developer in the room and who never learn to let go one iota: these managers are toxic and if you work for one as a software developer you will always be competing with this manager and being told that you are wrong and must do things their way. We need to move away from that approach and stop normalizing it.

Stay curious and learn new frameworks on the side as a manager, and glance at your team's code from time to time, absolutely. Be there to provide architectural guidance or help them see the benefit of using a certain methodology or design pattern, but stay out of the critical path because you'll only undermine or intimidate them and they won't ever achieve their full potential or exercise their full human agency.

Thoughtful and beautifully written as always, John. The idea of putting aside an identity as a 'coder' to assume that of 'manager' will strike a chord with many, I'm sure. The act of doing that might have become a psychological blocker (or 'bottleneck'). But you were able to set it aside. Now you've found a reason to take up this capability again and build something. That's great to hear.

The 'rationalization' you mention early in the piece to keep coding to 'keep your hand' in would, I think, be a justifiable one. But the idea that by "continuing to code as a manager you’re maintaining your ability to empathise with other engineers" sounds like a great strategy to bust that bottleneck in service to your goal.

And I'm looking forward to seeing the platform as it develops :)